Armenian Ceramics

While following the Via Dolorosa up the narrow, cobble-stoned streets of Old Jerusalem to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, I paused to catch my breath somewhere between the fifth and sixth Stations of the Cross and happened to see some ceramics in the window of the Jerusalem Pottery shop at house number 15. Pilgrim souvenir “kitsch” seems to ooze out of every nook and cranny of the Holy City, but these glazed tiles, illustrating Bible stories, stood out from all the sacred image polyester rugs, decal-icon plaques and gilded plastic crosses by the quality of their artistry—and luminosity. I was eager to learn more about them from the Armenian owners of the shop, the Karakashian family.

As the Christian population of Jerusalem slowly ebbs away through emigration, the Karakashians, along with the Balian and Sandrouni families, have remained to keep alive a tradition of pottery making, once developed by Armenian artisans in Kutahya, a leading ceramic center of the old Ottoman Empire. In 1918, before the British Mandate for Palestine began, the colonial authorities invited David Ohannessian, a master ceramics maker from Kutahya to come to Jerusalem and restore the tiles at the Dome of the Rock shrine. He was joined by potters from the Balian and Karakashian families.

The project was never realized, but the Armenian ceramic artists stayed on to form the Dome of the Rock tile workshop. Ohannessian is considered the founding father of the Jerusalem pottery-making trade and his distinctive style of Armenian tilework can be seen in murals in the famed American Colony Hotel and in the tri-lingual tile street markers of the Old City. The Balians and Karakashians set up their own ceramic workshop in 1922, and Ohannessian eventually left Jerusalem for Beirut in 1948, but his ceramic style has been continued by the Sandrouni Brothers, who established the Armenian Art Center in 1983.

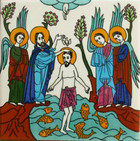

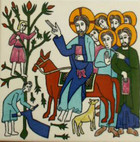

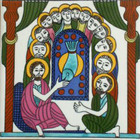

The elegantly simple compositions on these hand-painted, polychrome, ceramic tiles, depicting the life of Christ, draws on Greek, Coptic, and Assyrian iconography, as well as ancient Armenian illuminated manuscripts. Many are copies of Kutahya tiles from the early 18th century, which can be seen in the Armenian Cathedral of St. James in Jerusalem. As the story goes, they were originally intended for the Church of the Holy Sepulcher but were never installed in yet another of those wearisome confessional disputes among the Christian communities, sharing custody of the shrine, which continue to this day.

To reach a younger market, the Karakashian family at Jerusalem Pottery launched a line of tiles in a cartoon-like style, adapted from original designs by Harry Araten, a Moroccan-born Jewish artist who settled in Israel in 1968, best known for his children's book illustrations. The gallery includes whimsical images in the new format of Noah in the Ark, the Rescue of Baby Moses, David and Goliath, and the Flight into Egypt.