New Iconography of Lviv I

My first visit to the West Ukrainian cultural capital of Lviv in the summer of 2017 was a voyage of discovery. I came in search of a new style of iconography and found it a short walk away from the city's historic Market Square in the ICONART Contemporary Sacred Art Gallery, occupying two storefront rooms on a side street of the city's old Armenian quarter. I joined a crowd of mostly young art lovers gathered on a pleasant evening for the opening of the solo exhibition of Lviv Painter Natalya Rusetska on the theme Agape: From Creation to Salvation with keen anticipation. The show proved to be an eye-opener in the truest sense of the word.

Spaced along a wall of the tiny show room, a row of uniformly sized panels painted in muted colors depicted the first six days of Creation with painstakingly lined figurarive forms on geometric backgrounds. The seventh day was illustrated by an ethereal icon of Christ in Glory, preparing the viewer for images of the Passion. Christ as both the maker and redeemer of the universe appeared in a stylized Crucifixion scene set among the wonders of Creation, bringing together the themes of the show. Abstract modernism combined here with the detailed markings of manuscript miniatures.

Galleries featuring modern sacred art are a rare commodity. One specializing in contemporary iconography is a Pearl of Great Price. The ICONART website came up one day during an internet search for modern Madonnas. Looking at holy images in various modern styles, often made on unusual grounds like glass, “found” objects, and metallic tapestries, I realized the special role this gallery in Lviv could play in pushing the boundaries outward of a conservative sacred art form traditionally based on the copy of historic prototypes. This was worth a pilgrimage to the old East Bloc to see the real thing.

That Lviv should be the home of an experimental school of iconography came as no surprise to me. Known, variously, as Lwow, Lemberg, Lvov, and, now, Lviv, the city has been a historic crossroads of different cultures ruled (and occupied) in modern times by the Poles, the Austrian Habsburgs, Tsarist Russians, the Nazis, and Soviet Communists. It also lies on the boundary where the Byzantine East meets the Latin West. The dominant faith in the region is Ukrainian Greek Catholicism, which claims allegiance to the Holy See in Rome but follows the Eastern Orthodox form of worship, including the veneration of icons.

Stalin was suspicious of this “Latinized” Orthodox faith community with links to the Vatican. When these once Polish regions of West Ukraine were annexed by the Soviet Union at the end of World War II, the Kremlin engineered a one-sided merger of the Ukrainian Greek Catholics with the Russian Orthodox with Ukrainian church property (and its sacred art holdings) passing to the Moscow Patriarchate. Greek Catholics worshipped in the underground for almost 45 years, until Mikhail Gorbachev restored their legal status in 1989.

The new iconography is playing a key role in helping Greek Catholics revitalize a culture of sacred art-making all but lost to them during a half century of Soviet persecution, when the only images most of the faithful kept were holy cards in a syrupy-sentimental French Catholic style. There are schools in Lviv teaching traditional iconography, where students replicate sacred images of the 15th century—considered the Golden Age in Ukrainian liturgical art—working from photo enlargements of historic originals. The new iconographers take a different approach, using such time-honored techniques in distinctly individual ways.

These contemporary icon-makers in Lviv find inspiration in an eclectic pre-World War II sacred art scene. Under the patronage of Ukrainian Greek Catholic Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky, holy image-makers worked in Viennese Secessionist, Symbolist, Art Nouveau, Neo-Byzantine, Art Deco, and early Modernist styles. Most of the new iconographers are graduates of the Sacred Art Department at the Lviv National Academy of Arts, founded and directed by Iconographer Roman Vasylyk, where they learn traditional icon painting with tempera on wood, plein air painting, life drawing, mosaics, encaustics, icon-screen design, and fresco and grafitto work on plaster..

As I had discovered, the best place in Lviv to see the new sacred art on public display is ICONART, the brainchild of local businessman, Kostyantyn Shumsky. He was interested in buying a contemporary Greek Catholic icon and turned to art historian and theologian, Markiyan Filevych, for advice. They both saw the possibilities in creating a special niche art venue in Lviv, devoted to a type of modern sacred imagery, different from traditional church art. ICONART opened its doors in 2010 with Shumsky as owner and Filevych as curator—a display of commercial daring-do unimaginable these days in the secularized West.

On my first internet visits to the gallery, I was particularly impressed by the number of women icon-makers in its listings and by the works of four artists, in particular—Rusetska, Ivanka Demchuk, Ulyana Tomkevych, and Lyuba Yatskiv. Soon other women iconographers would join my listings. I wondered if this was a new feminist sacred art school in the making but learned in Lviv that women have always been anonymous icon-makers. The new freedom to pursue individual styles and sign pieces has simply brought them out of the shadows and won them long-denied recognition.

Ivanka Krypiakevych-Dymyd, a contemporary icon-maker whose solo show in 2010 launched the ICONART gallery, filled me in on the historical details. She was fortunate to have a Soviet-era art teacher who treated iconography as a historic school of art to be studied, but two generations of clandestine Greek Catholics entered freedom largely ignorant of their cultural heritage and emotionally bonded to bad art. As a “founding mother” of the new iconography, Krypiakevych-Dymyd met head on the first wave of hostility from post-underground faith communities who dismantled her icon screens because the images were considered too different. Acceptance has slowly come with time.

Comparing four images of the Virgin Mary in my collection from my starting quartet of new women iconographers, you can readily understand how the new style of iconography might appear revolutionary to traditional Greek Catholics, used to the visual conformity of sacred imagery. Yatskiv offers an intriguing variation on the historic prototype of the Virgin Who Shows the Way, where an older Christ child turns toward his mother in holy conversation. Demchuk gives us a mysteriously half-hidden Madonna and Child enveloped in incised gold decorations suggesting the art of Gustav Klimt and the Vienna Secession.

In two Nativity scenes, Tomkevych and Rusetka both follow the Orthodox iconographic tradition of depicting the Virgin Mary stretched out on the ground after giving birth to the Christ Child. She is seen in splendid solitude in Tomkevych’s variation, "pondering all these things in her heart" on a carpet decorated with Ukrainian floral folk art designs. Rusetska emphasizes the importance of the Incarnation of God for the entire cosmos in her icon of the Birth of Christ, a theme central to her summer solo exhibit, showing the characters from the Nativity narratives on a planet Earth suspended in space.

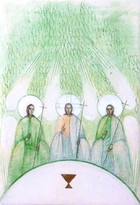

Rusetska places at the modernistic end of the style spectrum, abstracting her forms in ways that suggest the contemporary icons of the Polish Modernist painter, Jerzy Nowosielski. In the Virgin Who Shows the Way in Glory she creates a sense of transcendent weightlessness by setting delicately-rendered, stick-like figures in decorative sequences against a background of muted color washes. In the Resurrection, Rusetska draws on the Latin motif of Christ rising out of the tomb. His stylized, elongated body evokes the mystical traditions of Eastern Orthodoxy. She presents an Orthodox variation on the theme in The Harrowing of Hell. The Holy Trinity offers a verdant variation on the traditional iconographic convention of presenting God in Three Persons as the three angelic visitors to Abraham.

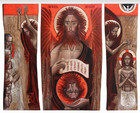

Yatskiv works in a style conforming more closely to the traditional Byzantine manner. Her large panel painting of Christ Ruler of All in my collection offers a strikingly new variation on a prototype seen in a 13th century mosaic of Christ in the Hagia Sophia (Holy Wisdom) church in Istanbul. In contrast to the traditional static frontal image, Yatskiv offers us a dynamic Savior in three-quarter profile who still engages us with his eyes. His hair and garments seem numinously wind-blown. The same warm palette of fire and earth tones appears in a companion piece of the Virgin Who Shows the Way, the John the Baptist triptych, and the Flight into Egypt, where she departs from traditional depictions of the scene by drawing our attention to a mature and authoritative Christ Child.

Holy Wisdom is one of the most ancient motifs in Eastern Orthodox art. Yatskiv gives it a decidedly modern twist in her icon of Sophia (Holy Wisdom) and Christ. Sophia (“wisdom” in Greek) often takes feminine form in sacred art. In the Yatskiv icon, Wisdom appears as a crowned angel in womanly form who meets Christ at the Eucharistic table, a image, Yatskiv says, “women will understand,” showing the feminine and masculine aspects of God, as revealed in the Creation story, where humans are made“in the image of God…male and female he created them. (Genesis 1:27, NRSV).”

Tomkevych makes icons that are neither 15th century replicas nor ultramodern. Trained as a watercolorist, she works with light applications of paint, mostly in variations of red and blue, drawing on Ukrainian folk art motifs like the pattern from traditional embroidery that appears on the table cover in Tomkevych’s variation on the Last Supper. Images showing a central portrait of a saint, fixed in eternity, framed by tiny visual vignettes from their lives are a popular genre in Orthodox sacred art. In Tomkevych’s icon of the Life of St. Nicholas, she shrinks the size of his heavenly portrait to focus our attention on the earthly miracles and good works of this much-loved intercessor She uses a similar four story panel composition in Love Your Neighbor in depicting the six acts of mercy (three are combined in the lower right image of hospitality) mentioned by Christ is his account of the Last Judgment in the Gospel of Matthew.

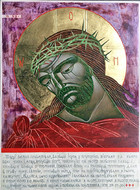

Tradition and modernity come together in Tomkevych's contemporary depiction of an ancient prototype of a miraculous image of Jesus known as the Savior Made Without Hands, which Christ is said to have left on a towel, sent to heal the ailing Syrian King of Edessa. Tomkevych uses variations on the traditional blue and red palette of Christ imagery in subtle and expressive ways in this unusual portrait in the round, reshaping the cloth on which the holy image miraculously appeared into the Cross. The suffering face of Jesus appears crafted from metal plates in Tomkevych's modern reworking of the Mocking of Christ motif.

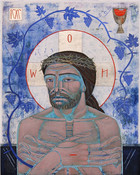

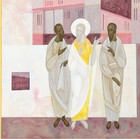

The youngest of my original quartet of women icon-makers, Demchuk is an artist in search of a style. Moving on from the fin de siècle Viennese icon of the Madonna and Child, Demchuk created a fully embodied Christ more typical of Western art of the Passion in her icon of the Holy Shroud, a cloth with an image of the Dead Christ used in the Good Friday liturgy of the Eastern Orthodox Church. In her most recent works, Demchuk has moved toward an abstracted mystical style, paying homage to the famous 15th century icon of the Holy Trinity by Andrei Rublev in a vision of diaphonous holy beings in a white celestial space.

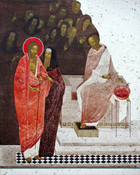

Demchuk's icon of Pilate Condemning Jesus to Death, originally intended to be the first image in a Stations of the Cross cycle, takes this style to a higher level. The mockers of Christ occupy a sepia-toned moment of sacred history, torn like a scroll to reveal the eternal whiteness of Divine purpose underlying human affairs. Christ's vivid red garment marks him as the sacrificial lamb, just as the water Pilate uses to wash his hands and absolve himself of responsibility in the Crucifixion is blood-colored. The way to Golgotha, marked by black and white tiles, leads out of the picture space and into God's plan for human redemption.

It is already possible to talk of a “younger generation” of women icon-makers, born after Demchuk in the 1990s, who are purposefully making their own mark on contemporary iconography. Many of them are students of Yatskiv from the Sacred Art Department of the Lviv National Academy of Arts.

Icons from Kateryna Shadrina can be immediately identified by their bold, expressive use of unconventional palettes like the red, green, and purple-tinted Harrowing of Hell and the rich mixing of colors and tonal effects in The Ascension. Heaven and earth seem to meet in kaleidoscopic explosions of color in depictions of the Nativity and Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane, where sacred events unfold, quite literally, in a divine limelight. These variegated images remind us that pure white light is composed of all the hues of the spectrum. Fiery colors dominate her icon made in time of war of the much venerated Protection of the Mother of God, where the Virgin provides a safe space for a grieving couple, a disabled man on crutches, and a youth tending a wounded dove under her extended mantle.

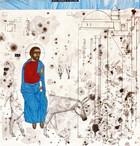

Khrystyna Kvyk combines Byzantine forms with Cubist geometrics and an Art Deco elegance of line to create a numinous image of Christ's Post-Easter encounter with two disciples on the Road to Emmaus where the Risen Lord stands out in a gleaming gold garment concealed by his cloak.

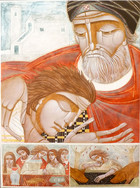

Khrystyna Yatsyniak brings together Byzantine styling with a modern feeling for line and abstraction of form in Pieta, where we see the Virgin Mary in close-up bending over the body of Christ taken down from the Cross in gritty olive greens and gray. In Yatsyniak's variation on this time-honored theme of Latin Christian art, the mourning mother reaches out to touch the face of her son, so peaceful in death, in a gesture that brings to mind Eastern Orthodox icons of Mary and the Christ Child whose cheeks touch in a loving embrace.

Kateryna Kuziv places Byzantine-styled figures in minimalist, monochrome paint-blot backgrounds with a visual texture similar to Demchuk’s work in her icons of the Triumphal Entry and the Descent of the Holy Spirit. Broad swaths of blue signal divine activity in the human realm. The “canon” she upholds is not any traditional style of visual representation but theological truth, expressed in ways “appropriate to the present day.” Says Kuziv: “A person who does not have an extensive religious knowledge should still be able to understand the message of the icon—potentially leading them to church.”

Hlafira Shcherbak applies contrasting colors in unusual ways, making creative use of white space and defining architectural outlines. Her icons in the Collection of Christ the Ruler of All and the Virgin of the Sign were made as a diptych on similar rounded panels. What looks like an abstract autumnal forest above Christ appears below the Virgin Mary in the companion image, where she reveals to us the infant Jesus in the circle of her womb. Says Shcherbak: “My art is about feelings and experiences, a dialogue and process of co-creation with viewers in all their differences."

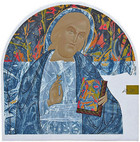

When my first trip to Lviv was coming to an end, I met with Krypiakevych-Dymyd to share my excitement over this new school of sacred art. She convinced me, as the son of a baptized Byzantine Catholic, to find an “intercessor” to help in my mission of collecting and promoting contemporary sacred art. Who better, she said, than the broad-minded, art-loving Metropolitan Sheptytsky? Copied from a photograph, she created an icon for me of the aging prelate, jotting down some thoughts before an icon of the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child, to inspire a not-so-young art collector to come back to Lviv. I have made the trip two times since then.

ICONArt Contemporary Sacred Art Gallery, Lviv, Ukraine

Agape: From Creation to Salvation Exhibition, ICONArt Contemporary Sacred Art Gallery, Lviv, Ukraine

Natalya Rusetska

Lyuba Yatskiv

Ivanka Demchuk

Ulyana Tomkevych

Natalya Rusetska

Natalya Rusetska

Natalya Rusetska

Natalya Rusetska

Natalya Rusetska

Natalya Rusetska

Natalya Rusetska

Lyuba Yatskiv

Lyuba Yatskiv

Lyuba Yatskiv

The Flight into Egypt

Lyuba Yatskiv

Ulyana Tomkevych

Ulyana Tomkevych

Love Your Neighbor

Ulyana Tomkevych

Ulyana Tomkevych

Ulyana Tomkevych

Ulyana Tomkevych

The Prodigal Son

Ulyana Tomkevych

Ivanka Demchuk

Ivanka Demchuk

Ivanka Demchuk

Kateryna Shadrina

Kateryna Shadrina

Kateryna Shadrina

Kateryna Shadrina

Kateryna Shadrina

Kateryna Shadrina

Khrystyna Kvyk

Khrystyna Yatsyniak

Kateryna Kuziv

Kateryna Kuziv

Hlafira Shcherbak

Hlafira Shcherbak