French Belle Epoque Illustrations

Few historical eras have so captivated the modern imagination as Belle Epoque France, the “Beautiful Era” spanning the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War (1871) and the outbreak of World War I (1914). The can-can revues at the Moulin Rouge cabaret, immortalized in the poster art of Henri de Toulouse Lautrec, have given these years an alluring aura of bohemian decadence, but it was also a time of experimentation, heralding the modern age to come. An upstart Spanish Artist, Pablo Picasso, broke every rule in art academy books with his painting, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon; Russian Émigré Composer Igor Stravinsky provoked a riot with his ballet score for The Rite of Spring; Physicists Pierre and Marie Curie discovered new radioactive elements; and Engineer Gustave Eiffel astounded the world with a 300 meter-high, lattice-work, wrought iron tower for the 1889 Paris Universal Exposition.

What was La Belle Epoque for some was Le Fin de siècle for others, the last gasp of a century gone wrong and a time for revanche, not only settling scores for the humiliation inflicted by the Prussian army in 1871 and the “bloody week” suppression of the Paris Commune revolt that immediately followed but also for grievances dating back to the 1789 Revolution and the fall of the Ancien Regime. Governments came and went with such alarming frequency, it was a miracle the cobbled-together Third Republic survived as long as it did. Not that its progressive, anti-clerical supporters would have dared to use such a word. They were engaged in a no-holds-barred culture war with anti-republican, monarchist-minded conservatives in the Roman Catholic Church and the military that escalated into the bitterly divisive Dreyfus Affair, when a French artillery officer of Jewish descent was convicted in 1894 of spying for the Germans on trumped up evidence

However you label this age of contradictions, it saw the birth of what we would now call popular culture. The republican-royalist battle for the heart and mind of Belle Epoque France played out before an audience of unprecedented size and scope from counts to salesclerks thanks to a boom in illustrated newspapers and picture magazines made possible by new printing technologies and a landmark 1881 law relaxing controls on the press. The institutional church suffered a major defeat in its holy war against secular republicans with the passage in 1905 of legislation on the Separation of the Churches and the State, and the notion of what was once considered “sacred art” was blown wide open by illustrators, engaged in the struggle for and against the secularization of France. It was enriched by the Symbolist movement, which left the liberal-conservative confrontation behind to pursue mystical realms beyond the bounds of scientific certainties and traditional religious dogmas.

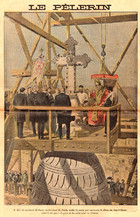

Curiously enough, one major target of pictorial polemics in the caustic cultural conflict was the Sacre-Coeur Basilica. Like the Eiffel Tower, this white-domed church on the Butte Montmartre is now such an iconic landmark of Paris, it is hard to imagine radical republicans once tried to block its construction. They were incensed a shrine whose very name summoned up the Sacred Heart of Jesus cult of the Ancien Regime should have been sanctioned by the state and positioned on a site associated with the beginnings of the blood-drenched Communard uprising. For them, it was nothing less than “an incessant provocation to civil war.” The Catholic press, for its part, just as deliberately celebrated key moments in the four-decades it took to build their church in expiation for the sins of the past with images like the 1899 chromolithograph in the Collection of the blessing of the cross atop the basilica.

In the secularist propaganda assault on Sacre-Coeur, Illustrator Theophile Steinlen turned the basilica's trademark dome into a triple tiara worn by a ghoulish spider-pope, spinning webs from the Montmartre Butte to ensnare multitudes of the credulous. The caricature was reproduced in a 1902 issue of L’Assiette au beurre (literally, “The Butter Plate”), an anarchist-leaning, illustrated weekly, active from 1901 to 1912, which skewered the sacred cows of bourgeois society. The magazine took up the battle against Catholic France's holy site once more in a 1911 edition with a portfolio of satirical sketches made at the basilica by an unknown artist (most likely, Rene Georges Hermann-Paul) replete with anti-clerical cliches of obese priests in barely-buttoned soutanes, desiccated dowagers receiving the host, and speculators in “blessed” souvenirs.

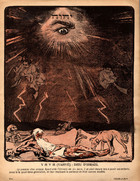

The secularists, in turn, were spoofed in a 1913 caricature from B. Brousset, where two nattily-dressed railway workers rebuff an old-fogey “demagogue” who tries to dissuade them from visiting the Basilica. Brousset worked for Le Pelerin (The Pilgrim), first printed in 1877 and continuing to this day. The illustrated weekly was one of the most popular of thirty-some Belle Epoque religious periodicals from La Maison de la Bonne Presse, the publishing house of the Assumptionist Order. Brousset's images frequently promoted conspiracy theories of a “Jewish-Masonic” threat to Catholic France, widespread among anti-republicans. One cartoon in the Collection from 1912 shows a Freemason in an apron with the square and compass emblem of his order, contemplating the “red harvest” of knives and revolvers its irreligious principles have sown. A second caricature shows a stereotypically Semitic-featured “city-slicker” progressive accosting a villager on his way to Mass.

Brousset inherited his poison sketch pen from Achille Lemot, a cartoonist at Le Pelerin from 1895 until his death in 1909, who was responsible for giving the journal’s illustrations a more aggressive edge. Typical of Lemot's style is the 1902 caricature of “France Catholique," embodied in a towering, fair-haired medieval knight in armor taking on cowering, pint-sized Jews and Masons in an arena. Other Lemot conspiratorial cartoons in the Collection from 1909 show a distortedly hooked-nose hunter with a slobbering mastiff waiting to ambush a village priest and a quartet of Lilliputian Masons engaged in their “eternal attempt” to pull down the Church's supporting column of the Crucified Christ. In one Lemot cartoon from 1905 on the theme of “The Separation of the Church and the State,” Masons in full regalia drive the faithful from their place of worship, belying the reassuring words of a blathering republican politician.

The French Catholic Church had more benign but highly effective weapons in the propaganda wars. Advances in color lithographic printing facilitated the cheap reproduction of holy images on prayer cards, picked up as souvenirs by a mobile French middle class, making pilgrimages to shrines like the Sacre-Coeur Basilica and the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Lourdes, erected on the site of an apparition of the Immaculate Conception to a peasant girl in the Hautes-Pyrenees in 1858. The prayer card designs coming from Catholic publishing houses near the St. Sulpice Church on the Parisian Left Bank were sweetly chaste, floral-entwined variations on the overripe realism of academic painters like William-Adolphe Bouguereau and appealed to a largely feminine market. Mass-produced artifacts in this “St. Sulpice Style” would soon go global, determining the taste in religious art of generations of Catholics in regions as far removed as the American Southwest and Western Ukraine.

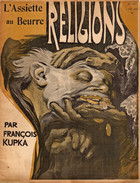

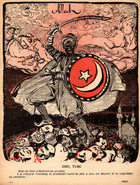

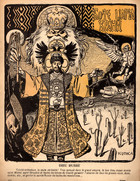

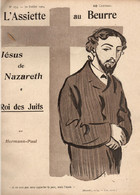

The secularists had the edge, when it came to the quality of their art. L’Assiette du beurre devoted a minimum of 16 full or double-spread pages every issue to photogravures and planographic reproductions on zinc plates of caricatures in a variety of styles by leading artists of the age. You can find lavish Art Nouveau drawings in a satiric send-up of the gods of this world in the 1904 spread, Religions, by Czech Early Modernist Francois (Frantisek) Kupka with a ghoulishly distorted cover image of priestly hands forcing gold pieces from the mouth of a dying man. Another issue in the same year features the Jesus of Nazareth: King of the Jews portfolio by Hermann-Paul with freely drawn illustrations of the sayings of Christ set in contemporary bourgeois Paris in the style of the artist's mentor, Toulouse-Lautrec.

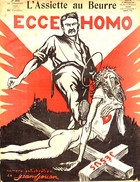

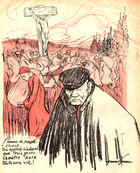

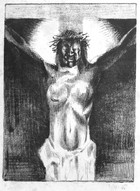

Caricatures sometimes crossed the line into blasphemy. Jules Grandjouan, a militant atheist aligned to the Revolutionary Syndicalist labor movement, lampooned the teachings of Christ as a tool of bourgeois oppression in the self-described "anti-Christian" Ecce Homo issue in 1906, where a sullen "man of the people" at the Crucifixion in the final plate claims Christ's three days of agony were nothing compared to his life time of suffering. The black and red cover image of a muscular worker kicking a flaccid, febrile Jesus, torn down from the Cross, anticipates the anti-religious propaganda of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. The Christmas issue for 1906, The Son of Man, offered a secular retelling of the Life of Christ, recast as a working class anti-hero named Emmanuel, born out of wedlock in an attic, who takes up with Madeleine, a woman of “bad life,” poses a threat to both church and state with his radicial opinions, and dies on the guillotine, illustrated with gritty drawings in a Post-Impressionist style by Dimitrios Galanis, a Greek ex-patriot friend of Picasso.

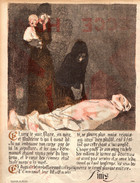

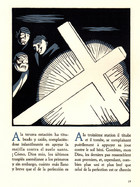

Not all religious-themed illustrations in L’Assiette au beurre were so deliberately provocative. Many secular-minded artists might have been enemies of the Church, but they were not ready to abandon Christ. He was also presented in the pages of the illustrated magazine as an impassioned opponent of institutional Christianity, protecting the poor and marginalized, as we see in a caricature from Louis Morin in a 1902 issue on Les Masques, where Christ in his "Behold the Man" incarnation defends a fallen woman from the hostile bourgeoisie. First translated into French in the 1880s, Russian novels were all the rage in Belle Epoque Paris, and there are echoes in several of the illustrated weekly’s pictorial narratives of Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s “Legend of the Grand Inquisitor” in The Brothers Karamazov, which tells of the cynical Catholic hierarch leading the Spanish Inquisition, who has Christ arrested for daring to appear on earth again and tells him the church can function better without him.

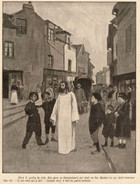

German-born illustrator Hermann Vogel used this motif of the return of Christ in the Easter and Christmas issues of L’Assiette du beurre in 1903. In the Easter suite, Redemption, Jesus is welcomed back to modern day Paris with full pomp and circumstance. He rejects the advances of the high and mighty in church and state only to find he has no place, either, among the working class. He spends the night under a bridge with the refuse of society, and in the final panel he weeps. Christ appears again on earth in the Christmas portfolio, From Bethlehem to Rome, this time, before the Pope, accusing him of everything from comporting himself like Pontius Pilate to fomenting religious wars. The Vicar of Rome makes a show of repentance but concludes in the final image that a humble and poor pope is no pope at all.

For the 1907 Christmas issue, Le Reveillon de Jesus (loosely translated, “The Holiday Celebration of Jesus”), L’Assiette du beurre selected cartoons from a stellar ensemble of Belle Epoque illustrators, including Emmanuel Barcet, the Polish-born Zyg Brunner, the Swiss-born Carlege (Charles Emile Egli), Artistide Delannoy, Ricardo Flores, and Francisque Poulbot. In this contemporary variation on the story of the Boy Jesus in the Temple, a young, beardless Christ gets a chilly reception at the Catholic sanctuaries, Protestant meeting houses and synagogues he visits on a tour of modern-day France, encountering strange religious practices, off-key music, kitschy art, and cash commerce. Only a cabaret dancer truly welcomes him, and he anoints her feet with oil. When Father Christmas tells the Boy Jesus no one cares about him anymore, he envisions his Crucifixion in the final panel and wonders if it was worth it all.

Adolphe Willette stands squarely at the intersection of Belle Epoque art trends, giving the era an enduring emblem in the decorative red windmill he designed for the Moulin Rouge cabaret. His use of religious imagery epitomizes the ambivalence of period illustrative artists in dealing with the sacred. A frequent contributor to L’Assiette au beurre, he created a compelling image of Christ for an issue on the French criminal justice system, showing him with nail-pierced hands in legal robes before the bar, anguished at not having won a case in 1903 years of defending the poor and oppressed. A Russian peasant stumbles under a cross, like Christ on his way to Golgotha, on a postcard Willette designed for a mailing campaign to Tsar Nicholas II, calling on him to bring peace to his own people, after he had initiated an international peace conference in 1899 in The Hague.

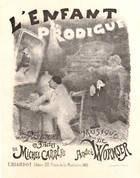

Willette would also use sacred motifs to pluck the heart strings in frothy illustrations like his 1893 print, La Cigale (The Grasshopper), where a repentant coquette sheltering among fallen park chairs by a snow-decked cross throws herself on God’s mercy. The title eludes to the “Ant and the Grasshopper” fable of 17th Century French Poet Jean de la Fontaine and the print includes a quote from the fabulist's contemporary, Dramatist Jean Racine, about divine provision for fledgling birds. Willette was enamored of the melancholy clown, Pierrot, a stock figure in French pantomime, and gave this holy fool his own hagiography, presenting him in one print as a foundling child raised by his namesake, St. Peter. In an 1890 poster for the musical pantomime, The Prodigal Son, Willette depicted a dramatic reunion between a father and his wayward boy, where both are Pierrots, one dressed in white, the other in black.

The poster reigned supreme among Belle Epoque mass-market illustrations, elevated to an art form by Jules Cheret. Dubbed “the father of the modern poster,” he promoted pleasure--not politics--in risqué, rococo-style compositions with voluptuous beauties, advertising everything from Dubonnet aperitif to lamp oil. Cheret took a painterly approach to lithography, designing texts in freehand so images would dominate. He broadened his palette by using separate stones primed in semi-transparent red, yellow, and blue inks to layer the colors and create mixed hues. From 1895 to 1900, Cheret offered enthusiasts of the new commercial art genre a monthly packet of four lithographic reproductions in reduced format of 256 posters by 97 of the best known illustrators of the period. Willette’s Prodigal Son print in the Collection was plate 14 in this Maitres de L’Affice (Masters of the Poster) series.

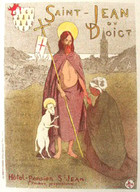

Religious-themed prints are few in the Cheret compendium. There are three posters by Etienne Moreau-Nelaton, a painter-art historian and commited Catholic, best known for the collection of Impressionist paintings he bequeathed the nation. His illustrations signal a new direction in sacred imagery of the period, blending the medieval and the modern. A peasant pays homage to John the Baptist in a hotel advertisement for the annual Grand Pardon in the Breton village of Saint Jean du Doigt, a procession dating back to the 15th century honoring a local relic of the saint’s finger (1894, plate 178). Costumed parishioners parade through Paris streets in a placard for a Nativity “Pastorale” at the historic St. Medard Church (1897, plate 118). As a medieval Madonna and Child look on, working class men and women contribute stones in a fund-raising appeal for the Notre Dame du Travail (Our Lady of Labor) Church (1897, plate 198). Erected in a Paris district that was home to construction workers at the universal expositions, the sanctuary boasts Eiffel Tower-like wrought-iron interior supports.

The materialist foundations of Republican France were eroding away on the eve of the new century, along with the sharp divisions between the religious and the secular. Artists of the Symbolist movement questioned whether reason and the scientific method were adequate means for understanding reality, believing ultimate truths were best approached through subjective experience, mediated through signs and symbols. Belle Epoque aesthetes were captivated by the concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) pioneered by German Romantic Composer Richard Wagner, melding together various art forms in one sensation-filled event. Parisians could get a taste of such multi-media happenings at the popular Le Chat Noir (Black Cat) cabaret, which enthralled audiences with "shadow plays," described by one contemporary critic as “a skylight open to the supernatural world.”

These pre-cinematic spectacles combining words, music, and moving images were the brainchild of Henri Riviere, an illustrator for the cabaret’s satirical weekly. He was inspired one evening to cover the opening in an existing puppet theater with a white napkin, then, made a cardboard cutout of policemen, placed the figures on the other side of the cloth, put on a light, and moved the silhouetted forms, while a singer crooned a ballad about "the cops". This impromptu shadow play proved so popular, Riviere went on to produce over forty such shows between 1886 and 1896. Some were so lavish the theater had to be enlarged so stage hands could maneuver multiple wood frames with silhouettes cut out of zinc, backed by colored paper or tinted glass, along runners set at three distances from an open flame projector. A 1894 wood engraving from the newspaper, L’Illustration, offers a glimpse backstage.

Capitalizing on the late 19th century enthusiasm for all things medieval, Owner Rudolphe Salis promoted Le Chat Noir at its opening in 1881 as “The Cabaret Louis XIII, founded in 1114.” The silhouette shows were often advertised as mysteres, medieval mystery plays. Like medieval theatricals, a Chat Noir performance might mix the sacred and the profane, as can be seen in a poster in the Collection from Riviere, bordered by silhouetted black cats in homage to the famous Steinlen cabaret logo. Top billing on this April evening in 1894 went to The Prodigal Son, “the biblical parable in seven tableaux,” accompanied by a reciter, a pianist, a violinist and “a voice from the wings.” It was followed by Pierrot the Pornographer.

Religious subjects in out-of-this-world stagings were a favorite with Le Chat Noir audiences. Billed as a “grand spectacle of enchantment,” The Temptations of St. Anthony, first performed in 1887, required forty tableaux changes. The images were accompanied by readings from a Gustave Flaubert novel about the desert saint and a musical score with operatic borrowings from Wagner and Charles Gounod. There was even a children’s choir in the wings intoning a hymn by Joseph Haydn! We can get a sense of just how spell-binding this production must have been in Riviere's opulent illustrations for a musical score of the shadow play published in 1888. The faithful desert hermit turns a blind eye in act one to all the enticements of contemporary Paris from the gluttonous pleasures of Les Halles market to the greed of La Bourse stock exchange and resists the seductive charms of the Queen of Sheba and the attractions of rival gods in act two to receive his divine reward in the finale, when he is taken up to heaven by angels.

The signature piece among Le Chat Noir shadow plays, performed over 500 times in Paris and on tour, was a Christmas pageant from Riviere, La Marche a l’etoile (The Procession to the Star), conceived as “a mystery play in ten tableaux,” which premiered on the Feast of the Epiphany in 1890. The light and sound spectacle opened with a panorama of the Christmas star over Bethlehem. Silhouetted shepherds, then, passed in review with their flocks, followed by soldiers, lepers, slaves, women, and the Three Kings. Fishermen in sailing boats also followed the star, and all found their way to the Bethlehem manger. It ended with a vision of angels around Christ on the Cross. The play called for three reciters, a musical ensemble with a cymbalist and cello and oboe soloists, as well as a chorus singing a cappella. A keyboard player must also have been included, since Composer Erik Satie is credited in one program.

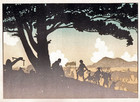

Few pictorial records exist of these ephemeral Le Chat Noir theatricals, but Riviere gives us a good approximation of what viewers might have seen in a shadow play production in the chromolithographic representations of tableaux, which he created to accompany Composer Georges Fragerolle's notes in illustrated musical scores for The Prodigal Son (1895) and The Procession to the Star (1899). They are stunning works of sacred illustrative art in their own right! Belle Epoque France was caught up in Japonisme, entralled with all things Japanese and the Asian sense of design. Riviere was an avid collector of Japanese prints and these recreated scenes from the shadow plays owe much to ukiyo-e (“floating world” art) woodcuts in their two-dimensional, silhouetted forms; linear bands of blended color; and cropped compositions, suggesting movement across the picture plane.

By placing his wood-framed tableaux at three removes from the back lighting, Riviere was able to give his shadow play images a sense of depth with the zinc cut-outs closer to the screen more clearly defined. He captures this illusion in the opening sequence of plates for The Prodigal Son, where the darker silhouette of the father in the foreground remains relatively unchanged, while the son comes and goes in a middle to back register of muted browns and greys. The progression of scenes even includes a sunset! In the musical score for The Procession to the Star, Riviere offers us truncated glimpses of what appears to be a sectional parade of uniformly colored figures and a flotilla of fishing boats bobbing in and out of view in their search for the Star, all set against a luminous background of subtly changing shades of blue.

Artist-Collector Moreau-Nelaton took the illustrated musical score a step further as a sacred art genre in his suite of 12 lithographs for an 1897 setting of the Stations of the Cross with score from Alexandre Georges and poems by Armand Silvestre, published the same year in which the artist's mother and wife perished in the horrific Paris Charity Bazaar Fire. Moreau-Nelaton's boldly sketched and highlighted scenes of the Passion move beyond pictorial story-telling to evoke an emotive response from the viewer in keeping with Symbolist aesthetics. Moreau-Nelaton’s illustrations for Les Grandes saints des petites enfants (Great Saints for Little Children), a story book on the lives of the saints he created for his children in 1896, are muted and insubstantial, as if the other-worldly figures on its pages might dematerialize before our very eyes.

The St. Sulpice Style of the conservative Catholic establishment would face its most serious challenge in the first decades of the new century not from republican secularists, who preferred a style of "naturalistic" art not so far removed from the sentimental realism of church imagery. It would come, instead, from artists of faith like Moreau-Nelaton and Maurice Denis, who enjoyed the patronage of the famous collector. While still in his teens, Denis emerged as a spokesman for Les Nabis (from the Arabic-Hebrew words for “prophet”), an off-shot of the Symbolist movement, which viewed art as an artificial construct of signs and symbols, expressing realities beyond surface appearances. Committed to renewing church art, Denis founded Les Ateliers d’art sacre (Studios of Sacred Art) to promote sacred art contemporary in style and accessible to the general public, an artistic mission detailed in a separate profile page.

The year was 1919. By then, the Belle Epoque was over. The “Beautiful Era” had fallen victim to World War I, which had raged across Europe from 1914 to 1918, leveling the ground for the modern age. The Great War also brought an end to the old conficts that had divided Belle Epoque France, turning erstwhile enemies in the battle over a secular state into nationalist allies in the defense of a shared motherland. Onetime secularist illustrators turned to religious themes.

A look at the career of Hermann-Paul offers an intriguing postscript to this survey of Belle Epoch sacred illustrated art. The anti-clerical caricaturist who once poked fun at the piety of the French bourgeoisie grew disillusioned with politics as the fabled era came to an end, treating religious themes with greater reverence, as we see in an undated lithograph of the Crucifixion in the Collection. After World War I, Hermann-Paul's favored medium was the woodcut, which he used to great effect in spare, two-tone illustrations for Via Crucis, a 1929 dual language edition of a Stations of the Cross narrative by Chilean Poet Augusto d'Halmar, translated into French by Hermann-Paul's wife. These boldly-outlined, geometrically-ordered scenes are a world away from the author's freely-sketched caricatures and cartoons from the Belle Epoque. In their abstract style, they are thoroughly modern; in their subject matter, deeply spiritual.

Eugene Damblans

Theophile Steinlen

Unknown (Attr. Rene Georges Hermann-Paul

Unknown (Attr. Rene Georges Hermann-Paul)

Unknown (Attr. Rene Georges Hermann-Paul)

Unknown (Attr. Rene Georges Hermann-Paul)

B. Brousset

B. Brousset

B. Brousset

Achille Lemot

Achille Lemot

Achille Lemot

Achille Lemot

Saint Sulpice Style Holy Cards

Francois Kupka

Francois Kupka

Francois Kupka

Francois Kupka

Rene Georges Hermann-Paul

Rene Georges Hermann-Paul

Rene Georges Hermann-Paul

Rene Georges Hermann-Paul

Jules Grandjouan

Jules Grandjouan

Demetrios Galanis

Demetrios Galanis

Demetrios Galanis

Demetrios Galanis

Louis Morin

Hermann Vogel

Hermann Vogel

Hermann Vogel

Hermann Vogel

Hermann Vogel

Hermann Vogel

Hermann Vogelillust

Hermann Vogel

Hermann Vogel

Zyg Brunner

Francisque Poulbot

Zyg Brunner

Aristide Delannoy

Adolphe Willette

Adolphe Willette

Adolphe Willette

Adolphe Willette

Adolphe Willette

Etienne Moreau-Nelaton

Etienne Moreau-Nelaton

Etienne Moreau-Nelaton

Georges Redon

Henri Riviere

Henri Riviere

Henri Riviere

Henri Riviere

Henri Riviere

Henri Riviere

Henri Riviere

Henri Riviere

Henri Riviere

Henri Riviere

Henri Riviere

Henri Riviere

Henri Riviere

Henri Riviere

Henri Riviere

Henri Riviere

Henri Riviere

Henri Riviere

Henri Rivieret

Henri Riviere

Etienne Moreau-Nelaton

Etienne Moreau-Nelaton

Etienne Moreau-Nelaton

Etienne Moreau-Nelaton

Etienne Moreau-Nelaton

Etienne Moreau-Nelaton

Etienne Moreau-NelatonSt.

Etienne Moreau-Nelaton

Etienne Moreau-Nelaton

Etienne Moreau-Nelaton

Rene Georges Hermann-Paul

Rene Georges Hermann-Paul

Rene Georges Hermann-Paul

Rene Georges Hermann-Paul