Holy Land Bible Illustrators

In a span of just eight years in the middle of the 19th Century, three books were published in England and the Continent that would shake the foundations of Western culture. In 1859, Charles Darwin proposed a new theory of Creation in his Origin of the Species. Karl Marx championed the working class in the 1867 economic manifesto, Das Kapital. And wedged between these two blockbusters was a theological tome of equally momentous content, The Life of Jesus, published in 1863 by Ernest Renan, a French seminary-trained philologist with too many doubts to enter the priesthood. In a direct challenge to traditional Church dogma on the divinity of Christ, Renan boldly wrote: “That Jesus never dreamt of making himself pass for an incarnation of God, is a matter about which there can be no doubt.”

David Friedrich Strauss, one of the first German Higher Critics, had earlier theorized that the supernatural strands of the Gospels were “myths” invented by the Early Church, but Renan was able to give the concept of a human Jesus greater historical verisimilitude with material gleaned while he was on a French archeological mission to the Eastern Mediterranean in 1860. In poetic pictures, Renan contrasted the verdant region of Galilee, where Jesus created his new faith based on freedom of the spirit and the fatherhood of God with the barren Judean surroundings of Jerusalem and its legalistic Temple cult that Jesus had vigorously opposed. Renan’s investigations convinced him that “for the historian, the life of Jesus finishes with his last sigh.”

The quest for the historical Jesus had began, and atheists and believers, alike, took up the challenge. Once exotic regions of the Middle East were now open to European and American travelers taking extended Grand Tours to sites in the Holy Land associated with the stories of the Bible. A veritable army of archeologists, historians, cartographers, ethnographers, and pillagers of antiquities had come in the wake of Napoleon’s military campaign in Egypt and Syria at the beginning of the century. Now, they bumped elbows with genuine and would-be biblical scholars, intent on investigating the historical truth of the Scriptures at excavation sites in lands largely controlled by the Ottoman Turks. Mark Twain made the trip in 1867 and immortalized the follies and foibles of Biblical Tourism in The Innocents Abroad, or The New Pilgrims’ Progress.

The growing interest in the historicity of biblical texts proved a bonanza for publishers of Bible atlases, dictionaries, and commentaries, who had already found eager buyers for Holy Land travel guides and artworks in reproduction of sacred sites. Quality images of Middle Eastern vistas were in such demand that notable period artists like J.W. M. Turner were recruited to “improve” on-the-scene sketches for suites of engravings like the 1836 Landscape Illustrations of the Bible Consisting of Views of the Most Remarkable Places Mentioned in the Old and New Testaments. The Turner prints of Bethlehem and Nazareth in the Collection with the artist’s trademark atmospheric touches of billowing clouds and direct sunlight were adapted from drawings by British Architect Charles Barry.

W.M. Thomson, an American missionary who had lived a quarter century in the Middle East, published a detailed compendium of geographical descriptions, historical notes, and every-day facts about the region in 1859 with the tongue-twisting title, The Land and the Bible, or Biblical Illustrations drawn from the Manners and Customs, the Scenes and Scenery of the Holy Land that was almost as widely read in its time as Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The tome was illustrated with plates similar to the Turner engravings, often tinted in later re-printings. As the author noted in his preface, he was more confident of the accuracy of the pencil sketches his own son provided for subjects as varied as female tattooing, wild mustard plants, and oriental customs at meals. The authenticity of sacred scenery and dress had never really concerned religious art-makers down the centuries. Byzantine iconographers used rivers, mountains, trees, and caves in symbolic ways, stretching out drapery to signify interiors. Early Renaissance masters in Italy decked the Wise Men in the brocades and satins of the luxury fabric trade of their time. The Jordan River in Piero della Francesca’s famous 15th century painting of the Baptism of Christ flows through a Tuscan landscape with the artist’s hometown visible in the background. Jesus and his disciples appear in variations of togas in Roman settings in the 17th century French Classicist paintings of Nicolas Poussin. The hunt for the Jesus of history set in motion by Renan and the Higher Critics changed all that.

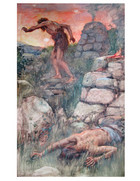

William Holman Hunt (1827-1910), a founder of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and devout Christian of eccentric views, visited the Holy Land four times between 1854 and 1892, explaining that his one desire was“to use my powers to make more tangible Jesus Christ’s history and teaching.” Hunt delved into the Talmud and other Jewish sources to better understand the Judaism of Jesus. For his first canvas in Palestine he chose the Levitical theme of the scapegoat, seeing this atonement ritual as a foreshadowing of Christ’s sacrifice. A meticulous painter, Hunt spent over two weeks at the Dead Sea making preliminary sketches. When his model goat succumbed to the hellish conditions, he finished the painting in his Jerusalem studio, posing another one in a salt water pool. The horrific details of The Scapegoat, seen here in a 1905 reproduction, disturbed Victorian viewers. As Art Critic John Ruskin acidly noted, Hunt seemed so absorbed by the theme he had forgotten how to paint a convincingly real animal!

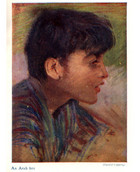

The guiding principle of this new Holy Land school of Bible illustration was articulated by William Hole (1846-1917), an artistic pilgrim to Palestine at the beginning of the 20th century, in his 1906 preface to The Life of Jesus of Nazareth, featuring 80 of his illustrations of Gospel themes. As Hole poetically opined: “In the backwaters of civilization, where the current of time flows past, leaving the manners and customs of a people unchanged, it is possible so to re-create the past, that pictures representing it may lay claim to a certain amount of historical accuracy. And thus it is in the land of Palestine, where observation of the primitive life of its inhabitants impresses the conviction that, in this respect at least, nothing of importance has changed; but that as it was in the days of Jesus Christ, so it is to-day.” The view that life in the Ottoman Empire at the turn of the 19th century was an ideal source for authentic biblical imagery may no longer be convincing, but it long held sway in the early modern era.

The gold standard for Holy Land Bible illustrations was set by J. James Tissot (1836-1902), in his magisterial work, The Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ: Three Hundred and Sixty-Five Compositions from the Four Gospels with Notes and Explanatory Drawings, first published in 1896. In the very title, the Anglicized French artist threw down the gauntlet to Renan. A famed chronicler of Belle Epoque society, Tissot had a conversion experience one Sunday in 1885, when he had come to Mass to make sketches for a Woman of Paris series. He spent the next ten years working on what came to be known as the Tissot Bible, journeying to Egypt, Syria, and Palestine in 1886-87 and 1889 to make preliminary sketches of their peoples and landscapes, a saga chronicled for his American publisher in McClure's Magazine in March 1899. The artist turned biblical expositor based his notes in the text on the Gospels and over 75 extra-biblical sources, ranging from the Talmud and the writings of Josephus to apocryphal literature and the visions of the 19th Century German Mystic, Anne Catherine Emmerich.

As Tissot explained in his introduction to The Life of Our Lord, “the imagination of the Christian world has been led astray”by religious artists down the centuries, who were “of one accord in ignoring the evidence of history and dispensing with typographical accuracy.” He saw himself as a man on a mission to set things right: “Attracted as I was by the divine figure of Jesus and the touching scenes recorded in the Gospel, I determined to go to Palestine on a pilgrimage of exploration, hoping to restore to those scenes as far as possible the actual aspect assumed by them when they occurred. For this, was it not, indeed, absolutely necessary to study on the spot, the configuration of the landscape, and the character of the inhabitants, endeavoring to trace back through their modern representatives through successive generations the original types of the races of Palestine, and the various constituents which go to make up what is called antiquity?”

To tell the story of Christ, Tissot selected excerpts from the Synoptic Gospels and John in the Latin Vulgate and an English or French translation, presenting the texts with decorative letter headings in parallel columns. His own disquisitions on a wide range of topics like Temple sacrifices, Jerusalem waterworks, semi-feral dog packs, acrobatic dancing, and fig tree cultivation appear in italic sections interspersed among the dual language scripture passages. Tissot was confident enough of his sources to offer a detailed biography of Mary Magdalene, conflating her story with that of Mary of Bethany, and give a running account of the Passion of Christ far exceeding the Gospel narratives in length and detail. He wrote with such familiarity about the Jerusalem Temple, the lay-out of its various courts and store rooms, and the color and facing of its stones that readers could readily accept the artist’s notion of himself as “the reporter for an illustrated paper in Rome under Tiberius.”

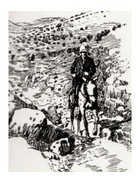

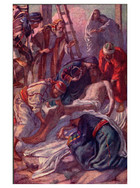

The Life of Our Lord is lavishly illustrated with Tissot’s 365 “compositions” in sepia/monochrome images and chromolithographs, both embedded in the text or tipped in as plates like the state-of-the-art print in the Collection of The Descent from the Cross, prepared by the artist’s French publisher to promote a luxury edition of the Tissot Bible. Separate chromolithographs like The Wise Men Journeying to Bethlehem were made from monochrome images in the book for the English language market. Just how closely the artist followed his mandate to bring the biblical narratives to life using material from his Holy Land sketchbooks can be seen by comparing the finished Gospel illustrations with drawings also reproduced in the text. Joseph can easily be matched with portraits of contemporary Jews. A well in Ain-Karim, traditional birthplace of John the Baptist, appears in a print of the Boy Jesus carrying a water pot. Christ preaches from a rock clearly visible in a drawing of the shoreline of the Sea of Galilee.

Such careful attention to “historical” detail did not preclude Tissot’s use of supernatural motifs. The artist spoke of his work on the final compositions derived from his Palestine sketches as a visionary process, where the biblical illustrations would often appear in completed detail in his mind’s eye. There are many other-worldly scenes in the text, going above and beyond the type of angelic apparitions you expect to find in depictions of the Gospels. An eerie ensemble of the hosts of heaven with flaming foreheads offer comfort to Christ following his Temptation in the Wilderness. Other angelic hands trouble the healing waters of the Pool of Bethesda, as described in John 5:4. On the day of the Crucifixion, a pair of seraphic angels mark the hours on a heavenly clock, while the embodied dead haunt the Temple precincts, and a troop of divine emissaries escort the soul of the repentant thief into Paradise.

Tissot’s meticulous rendering of the Passion with separate scenes devoted to the scourging of Christ’s face, the scourging of his back, the hammering in of the first nail, the nailing down of his feet--as well as images based on the Roman Catholic devotional cycle of the Stations of the Cross--did not go over well with conservative Protestant viewers who had gotten an early look at the artist’s watercolor cycle for The Life of Our Lord in promotional shows in London and across the U.S. Tissot fiercely defended his style of imagery: “Do people want me to compose an account of the Passion in the style of the poets of the Renaissance? Do they want a well-made crucified figure with a very white skin and three drops of blood at each wound to contrast with the pallor of the flesh? Such a crucified form is not mine, for it is not that of history. Those who are afraid of blood and of wounds, of flesh which turns blue when it is bruised, had better not look at my work and they had better not read the Gospel either.”

In the first decade of the new century, The Religious Tract Society, a Christian publishing group founded by missionary-minded Evangelicals in London in 1799, decided to print a new edition of the Bible in the King James Version with illustrations of the Scriptures—and nothing but the Scriptures. It found the perfect artist for this impeccably Protestant project in English Illustrator Harold Copping (1863-1932), a gifted portraitist who had created a well-received suite of images for a 1903 RTS printing of The Pilgrim’s Progress. Copping was commissioned in 1905 to come up with 60 color drawings on biblical themes chosen by the Society, 30 from the Old Testament and 30 from the New Testament, and sent off on an all-expense-paid tour of Egypt and Palestine. He was met in Haifa by his brother, Arthur, a seasoned newsman who would write up their adventures in the 1911 RTS publication, A Journalist in the Holy Land, replete with reproductions of sketches and watercolors by Harold.

Arthur’s travel memoirs offer a fascinating glimpse into biblical “fact-finding” expeditions of the period. The Brothers Copping journeyed in grand style on a Thomas Cook tour with eight guides, guards, cooks, and servants, dining off table clothes with silver settings in pavilion-tents once used by Kaiser Wilhelm II on an 1898 visit. Their circuitous trek on horseback followed a typical itinerary, beginning in the Crusader port of Acre on the Mediterranean and ending at the Dead Sea, taking in Nazareth, the Sea of Galilee, the Jordan River Valley, the Judean Wilderness, Jerusalem, and Bethlehem. Arthur does a good deal of harrumphing in the book about the squalor and incivility of the locals. With a distasteful note of Anglo-Protestant snobbery, he dismisses the Church of the Holy Sepulcher altogether as a sacred site: “One is shown sites and relics of which the genuineness is, as a matter of common knowledge, denied by authoritative persons. Skepticism in such matters prevents reverence—nay provokes resentment.”

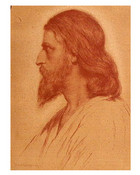

Copping the Artist produced fine on-the-scene pastel drawings and watercolor studies of Palestinian faces and scenery but completed the project in his studio in the Kentish town of Shoreham in a manner that would have met with Tissot’s decided disapproval. A London model provided the face of Christ and Shoreham neighbors posed for other biblical characters, often decked out in the headdress of a striped roller towel from the family kitchen. The Copping Bible, published in 1910, became an international best-seller and its images would be reproduced in numerous publications, shaping the biblical world view of many Protestant Sunday School children for decades to come. The artist would not benefit from the financial windfall; he was paid by contract for each piece without promise of royalties. The original Copping watercolor in the Collection of Cain and Abel can be seen here along with its copy in the Copping Bible and a large, tipped-in chromolithograph from the 1908 RTS portfolio, The Gospel in the Old Testament.

Among the top ranked Holy Land Bible illustrators only Elsie Anna Wood (1887-1978) could truly claim to have an insider’s knowledge of biblical locales. Wood was the daughter of a London commercial artist, who was unusual for his time in encouraging her to pursue an artistic career. Of good Baptist stock, she felt a call to the mission field and found a post at the Nile Mission Press in Cairo. As the news item,“Better Pictures for Moslem Children,” in a 1920 issue of The Missionary Review of the World quaintly reported, “the trained illustrator” Wood had been taken on to create “wholesome illustrated literature to counteract the cheap and demoralizing pictures for which a demand has grown up…largely due to the prevalence of the ‘movie.’” Wood only held the job for six months but the time spent in Cairo took her to Palestine and initiated her into the mysteries of the Middle East.

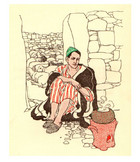

The would-be “missionary artist” was able to return five years later to Egypt through the London-based Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK), the oldest missionary arm of the Anglican Church, founded in 1698 to advance the Christian faith through publications and a global network of libraries. At a time when women illustrators were deemed best suited for children’s literature, Wood put her knowledge of Holy Land lore to good use in the 1930s series, Bible Books for Small People, making true-to-life drawings of the Good Shepherd warming himself at a brazier by a stone sheep fold; the Sower of the Seed tilling his land, scattering the seed, and and winnowing his harvest in the wind; and the Wise Men seated on the ground in the manner of oriental sages in a Persian miniature. Her images for the mini-book on the Parable of the Lost Coin are little ethnographic gems, showing a typical Palestinian woman retracing her steps through the chores of the day in search of a coin lost from her dowry veil.

Wood’s magnum opus is a cycle of watercolor and gouache paintings of the life of Christ destined for the S.P.C.K. Giant Picture Book and Gospel Picture Book series of Sunday school materials, published around 1950, offering six portfolios in two sizes, each with eight images and brief explanatory texts, on Gospel stories from the Annunciation through Pentecost with two additional folders on the parables, partly completed by Wood. She originally thought it would take only two years to create 50 illustrations; in reality, 35 years would pass before close to 100 of her pieces found their way into print. Wood believed that however juvenile her intended audience might be she needed to immerse herself in the culture of the Middle East. Like missionaries who study foreign languages, she was intent on learning the “picture language” of biblical locales--key visual details like the absence of shadows in intense daylight. As Wood later recalled: “Everything had to be noted and learnt, before I could begin to draw in a way which would be familiar and acceptable to the children who knew only their own country and its ways.”

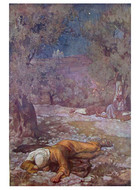

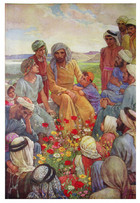

As meticulous in her research as Holman Hunt and Tissot, Wood stayed at a guest house in an Eastern Orthodox convent in the Garden of Gethsemane and went out at night into the olive groves to make sketches of the shadow and color effects of light filtering through the trees. She wanted to give as accurate a rendering as possible of the full moon of the Passover season in her illustration of Christ praying in the garden. Such attention to authentic details is evident in other poster prints in the S.P.C.K. series. Over the shoulders of Joseph and Jesus in their workshop in Egypt, we see dhow boats plying the waters of the Nile. The boy Jesus looks down on an accurate rendering of the village of Nazareth and its surroundings from a field abloom with local varieties of wildflowers. Wood's floral display in a poster of the Sermon on the Mount could serve as a handbook for Holy Land horticulture. The Master and his disciples recline to eat the Last Supper on a typical Middle Eastern woven palm mat, while Mary Magdalene meets the Risen Lord beneath a painstakingly drawn fig tree.

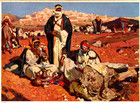

Dean Cornwell (1892-1960), the “Dean of American Illustrators,” made the journey to Palestine in May 1925 not for a Christian publishing house or a mission society but for the popular American magazine, Good Housekeeping. In a news item in the December 1925 issue with a photo of Cornwell sketching in Nazareth, the editors promised their readers one full-color reproduction a month in the new year of the artist's commissioned pieces, "making a beautiful and valuable portfolio of Bible-land pictures." A second series followed in 1927-1928. The serialized prints with text could also be purchased in book form. The City of the Great King (1926) offered “modern-day” glimpses of Bedouins in Bethlehem and a carpenter’s shop In Nazareth with tone poems by William Lyon Phelps, author of a syndicated inspirational column with millions of readers. Bruce Barton, who presented Jesus in his bestselling 1925 biography, The Man Nobody Knows, as the “founder of modern business,” wrote reflections on twelve scenes by Cornwell on the life and teachings of Christ for The Man from Galilee (1928).

Freed from the constraints of illustrating biblical texts or Sunday school teaching materials, Cornwell viewed sacred story and scenery in The Man from Galilee with an idiosyncratic, painterly eye. Omitting expected episodes from the life of Jesus, he chose to depict the parable of “The Man Who was Rich but not Wise” showing him as a pompous oriental potentate sitting with his wealth in clay jars in an airless cellar. (In the text, the arch-capitalist author, Barton, makes a distinction between “the love of money” and knowing its usefulness). Cornwell also gives us a different spin on the Prodigal Son, who resembles a vagabond enjoying the freedom of the road more than a repentant sinner heading home. At times, his artistry is so self-evident as to be distracting. In “The Washing of His Feet,” we must look closely to find Jesus and the foot-washing woman amid the jewel-box brilliance of its highly stylized and elaborated Art Deco composition. Cornwell’s caparisoned camels on the road to Damascus in The City of the Great King are such a visual delight we can easily forget this was the setting for the Apostle Paul’s conversion!

Margaret Tarrant (1888-1959) was already an established illustrator of children’s book, famed for her series on fairies, when the Medici Society, her longtime publishers, sent her in 1936 on a six-week artistic pilgrimage to Palestine. The trek was well-trodden by then and a hint of disillusionment creeps onto the pages of her diary, belatedly abridged and printed under the title, A Journey to the Holy Land, in 1988. As Tarrant put it: “The Mount of Olives—Gethsemane—The Brook Cedron—The Garden Tomb--what pictures these names bring to one’s imagination! Some prove to be more or less true pictures—others untrue. To one visitor a certain spot will seem full of reality and to be there will be one of the greatest moments of his life, while to another that place may be disappointing, but some others will satisfy him, and make his pilgrimage all he hoped.” In The Story of Christmas (1952), Tarrant used an interior watercolor of a Galilean home as the backdrop for the Adoration of the Magi and a colonnade from the Dome of the Rock appears in her rendering of the presentation of Jesus at the Jerusalem Temple, but sweetly cherubic manger scenes of the holiday card variety would remain the artist-illustrator's stock in trade.

The times were changing along with the audience for "authentic" biblical art. Younger generations of higher critics like Albert Schweitzer questioned the "demythologizing" assumptions of Renan's Life of Jesus in their own quest for the historical Jesus. The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls at the end of the 1940s dramatically recast the debate over the world Jesus lived in and the historicity of the Bible. A host of post-war translations of the Scriptures, beginning with the Revised Standard Version of 1952, underscored the importance of sacred texts by omitting accompanying images. With the advent of television and improvements in photographic reproduction, the market slumped for both secular and religious books with reproductions of works by established artists. Holy Land Bible illustrations soon became a thing of the past.

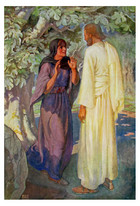

Fortunately for us, enough examples from its golden age remain in circulation today to remind us of the achievements of these intrepid, traveling artist-illustrators. In closing, we offer a selection of works by Tissot, Hole, Copping, Wood, and Cornwell, depicting the same four Gospel narratives--The Woman at the Well, The Feeding of Five Thousand, Jesus Healing the Sick, and The Crucifixion--as evidence of the creative and varied visual ways these artists found of retelling the Greatest Story Ever Told.

J.M.W. Turner after Charles Barry

J.M.W. Turner after Charles Barry

Uknown Illustrator with W. H. Thomson

W. H. Thomson

W. H. Thomson

W. H. Thomson

William Holman Hunt

William Hole

J. James Tissot

J.James Tissot

J. James Tissot

J. James Tissot

J. James Tissot

J. James Tissot

J. James Tissot

J. James Tissot

J. James Tissot

J. James Tissot

J. James Tissot

J. James Tissot

J. James Tissot

J. James Tissot

J. James Tissot

J. James Tissot

J. James Tissot

Harold Copping

Harold Copping

Arthur & Harold Copping

Harold Copping

Harold Copping

Harold Copping

Harold Copping

Harold Copping

Harold Copping

Harold Copping

Elsie Anna Wood

Elsie Anna Wood

Elsie Anna Wood

Elsie Anna Wood

Elsie Anna Wood

Elsie Anna Wood

Elsie Anna Wood

Elsie Anna Wood

Elsie Anna Wood

Elsie Anna Wood

Elsie Anna Wood

Unknown Photographer with Dean Cornwell

Dean Cornwell

Dean Cornwell

Dean Cornwell

Dean Cornwell

Dean Cornwell

Dean Cornwell

Dean Cornwell

Margaret Tarrant

Margaret Tarrant

Margaret Tarrant

Margaret Tarrant

Magaret Tarrant

J. James Tissot

William Hole

Harold Copping

Elsie Anna Wood

Dean Cornwell

J. James Tissot

William Hole

Harold Copping

Elsie Anna Wood

Dean Cornwell

J. James Tissot

William Hole

Harold Copping

Elsie Anna Wood

Dean Cornwell

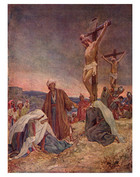

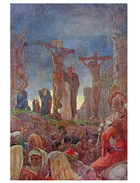

J. James Tissot

William Hole

Harold Copping

Elsie Anna Wood