East European Wood Carvings

The once abundant forests of Eastern Europe were a rich natural resource for people living off the land. They built homesteads from timber and heated them with wood; furrowed fields and harvested hay with wooden plows and rakes; wove cloth on wood frame looms made from thread spun on wooden spindles. And they dined with wooden spoons off wooden bowls seated on wooden benches at wooden tables. A storage chest might be decorated with floral patterns and dragon heads carved onto mead ladles but wooden objects were prized not for their beauty but their practicality. Break them—and there were plenty more where they came from.

One type of wood carving was valued for more than its usefulness—cultic objects. The earliest known wooden sculpture in the world is a 12,000-year-old totem pole preserved in a Siberian peat bog. Willow votive figurines from the Stone Age have also been found at lake bottoms in Poland. After Eastern Europe accepted Christianity in the 9th-10th centuries, shrines made from wood appeared in Roman Catholic regions beside roadways, along boundary lines, and at traditional sacred spots to offer solace and protection to travelers. When time took its toll, local carpenters and itinerant woodworkers made new markers copied from old ones and carved wooden figures modelled on revered Gothic and Baroque statues for rural chapels and home prayer corners.

The idea that rustic wood carvings of this kind should be considered “folk art” took hold in the 19th century when a sense of national identity grew among the subjugated peoples of Eastern Europe and a peasant class emerged from the newly liberated serfs. As cheap manufactured goods replaced hand-crafted household wares, land workers spent their fallow seasons carving toys and souvenirs, mostly from linden, alder, and willow wood, to sell at regional fairs, markets, and pilgrimage sites. In the modern era, foreign collectors with an eye for unusual craft pieces joined city dwellers with a nostalgia for their rural roots in creating a new demand for traditionally-styled wood carvings—encouraged by Communist era regimes in need of foreign currency.

Sacred works by contemporary East European woodcarvers in the Collection listings are as varied as the Pieta cut out off a single wood stump by Polish Woodcarver Wladyslaw Gruszczynski (1935-2011) from Radom and the multi-figured ensemble of Pope John Paul II praying with Christ in his Passion by Zbigniew Labuda (b. 1946) from Kielce, Poland. One especially popular motif in this assortment of religious pieces is the Pensive Christ (also known as “Man of Sorrows”), showing a thorn-crowed Jesus slumped in a thinker pose. The image can be seen in the gallery, stripped and clothed, in twelve variations. They are on carved panels and free-standing, unstained and polychrome, traditionally figurative and naïve in style. Four of the pieces replicate wayside shrines.

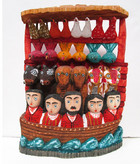

The Collection has a particularly fine assortment of works by three contemporary Polish woodcarvers —Tadeusz Kacalak (b. 1952), Anton Kaminski (b. 1947), and Andrzej Wojtczak (b. 1945)--considered to be the founders of a school of wood carving linked to the village of Kutno in the Polish heartland. The trio met at a folk art competition in 1975. They recognized similarities in their sculpted pieces and have promoted their distinctive style in exhibitions, folk fairs, and workshops. Kutno carvings are characterized by multi-figured compositions with frieze-like rows of stylized heads and repetitive decorative patterns. Typical examples in the gallery are the Kaminski sculpture of Noah’s Ark with four tiers of birds, beasts, and floating humans and his psychedelic image of St. George slaying the dragon in riotous polka dots.

Kaminski is the best represented Kutno artist in my listings with ten sculptures of the life of Christ. Wide-eyed angels with pageboy haircuts pier down on the Bethlehem manger and keep vigil with Mary in lamentation at Golgotha. Stylized floral garlands (and the white dove emblem of the Holy Spirit) repeat in sculptures of the Flight into Egypt and the Baptism of Christ. Wojtczak images of the Madonna of the Fields and Flowers, Christ the King, and the Resurrection show darker skin tones from his choice of wood. They have a more finished, almost molded, appearance but also engage the viewer with an unblinking gaze. My single work from Kacalak, a finely finished Crucifixion scene with repetitive praying hands, was purchased from the artist—born seven days before me in 1952!--during the annual Spanish Market weekend in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Religious faith undergirds the work of the self-taught trio—with a dash of playfulness. Wojtczak recalls how he, along with Kaminski and Kacalak, once specialized in images of Devil Boruta, a stock figure in Polish folklore, until a stint in prison in the 1980s for his anti-Communist views introduced him to real demons! He devotes more time now to images of the Pensive Christ, whose bright red cloaks are not always to clerical tastes. Kaminski sees himself these days as an angel-maker, joking that he sculpts them “from life” in the skies above Kutno. He feels a call “to do something valuable for God and humanity.” The sentiment is shared by Kacalak. “This is a gift from God,” he says. “How else can I explain the fact that when I pick up a chisel, I sculpt like artists who graduated from academies of fine arts?”

Roman Sledz (b. 1948) from the village of Malinowka in the Lublin region of Eastern Poland has followed a singular path as a wood carver. A onetime tractor drive and construction worker, he cut out his first wood image of a human face when he was 20, after reading a newspaper account of two local brothers who made good as wood carvers. Linden trees soon disappeared from the family farm as Sledz pursued his newfound craft, but his roughhewn pieces were largely dismissed by the state-controlled art establishment as too crude, until the German journalist and folk art collector, Ludwig Zimmerer, showed an interest. Sledz gained official recognition in the late 1970s, but his growing circle of foreign admirers also brought unwelcome attention from the secret police until the fall of Poland’s Communist regime in 1989.

Sacred themes in unusual variations make up the bulk of the Lublin woodcarver’s work. Sledz grew up in the world of the Bible, guided by his widowed mother who prayed daily before holy images. Compared with the doll-like figure groupings from Kutno, Sledz brings an expressive realism to his gouged out faces with their paint-dot eyes and slanting pencil-line brows. His sacred scenes have an emotional immediacy conveyed by the sharp-edged marks of his cutting tools and stray paint blotches on bare wood. Viewing three depictions of the Crucifixion from Sledz in the Collection, you can easily understand why he has been called the Master of the Way of the Cross. Says Sledz: “The sadder the sculpture the more it touches me and the more beautiful it seems.”

South of the Polish border at the Tatra Mountains in Slovakia, Jan Krlicka (b. 1954) creates his own variations on the Pensive Christ in a forest cottage near the city of Presov. The Czech-born wood carver showed artistic ability as a child growing up in Slovakia, but he was denied entry into art schools during the Communist era because of his “suspect” social background as the son of an activist priest in the Byzantine-rite Catholic Church—a branch of Catholicism that allows married clergy. Krlicka received vocational school training and found lucrative work as a demolition expert at construction sites, only turning to art making in his forties after the 1989 Velvet Revolution toppled the Communist regime.

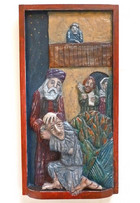

A self-taught artist, Krlicka first gained recognition at regional folk art exhibitions and was befriended by Dusan Poncak, a Slovak sculptor known for his monumental works in an expressive figurative style. Krlicka’s wood carvings show the influence of artists as diverse as Master Pavol of Levoca, the medieval sculptor who created the world’s tallest Gothic altar in wood in the St. James Basilica in the Slovakian city of Levoca and Modern Colombian Painter and Sculptor Fernando Botero of the super-sized figures. Krlicka enjoys making art that tells a story and finds bas-reliefs better suited for illustrating narratives than three-dimensional sculptures as can be seen in his relief panel in the Collection of the Return of the Prodigal Son with its multiple “characters.”

Krlicka first caught my eye with a whimsical variation in wood of the Last Supper. This was no staid line-up of interchangeable disciples but a boisterous bunch with distinctive faces. Jesus seemed to be raising his hands in a call to order as well as blessing the bread and wine! Krlicka further confirmed his skill in illustrating complex biblical narratives in compact compositions in a commissioned piece on eyewitnesses to the Crucifixion that includes the Holy Women and St. John, the scoffers, and the Roman guards. He followed this with a third panel in what has become a Passion of Christ triptych, incorporating all of Christ’s Post-Resurrection appearances from his encounters with the myrrh-bearing women at the tomb and with Doubting Thomas to meeting his disciples gone fishing on the Sea of Galilee.

Sacred themes may be few and far between these days in what is considered to be “fine art,” but they are fine and flourishing in the folk art of Eastern Europe. In this Post-Modern period of taped-banana installations and Non-Fungible Tokens, it is wonderfully counter intuitive and even heartening to know there are still wood carvers who make modern variations on time-weathered roadside shrines and work with hand tools to create religious artifacts just as artisans and carpenters have done down the centuries before them.

Wladyslaw Gruszczynski

Zbigniew Labuda

Pensive Christ I

Pensive Christ II

Pensive Christ III

Anton Kaminski

Anton Kaminski

Anton Kaminski

Anton Kaminski

Anton Kaminski

Anton Kaminski

Anton Kaminski

Andrzej Wojtczak

Andrzej Wojtczak

Andrzej Wojtczak

Andrzej Wojtczak

Tadeusz Kacalik

Roman Sledz

Roman Sledz

Roman Sledz

Roman Sledz

Roman Sledz

Jan Krlicka

Jan Krlicka

Jan Krlicka

Jan Krlicka