New Iconography of Lviv II

Catching the No. 8 tram from the Old Town of the West Ukrainian city of Lviv, I headed southeast toward the suburban district of Sykhiv to visit the Church of the Nativity of the Holy Virgin, considered to be the best example of contemporary Ukrainian Greek Catholic architecture in this border region near Poland. The strikingly modern sanctuary from Canadian Architect Radoslav Zuk was hard to miss with its five gilded domes and pure-white walls in variations of the egg, the cube, and the tube. It looked as if it had landed from outer space in a dreary neighborhood of Soviet-era housing blocks, resembling upturned match boxes in concrete.

Waiting at the entrance, Iconographer Sviatoslav Vladyka guided me through the visual “program” of wall paintings and mosaics he designed for the interior of the church, completed in 2001. I felt immediately enfolded in diffuse light from the tower wells of the five domes, reflecting off countless golden mosaic tiles in the cupolas and the altar space. The three tiers of images on the walls of Christ and the angels, the apostles and prophets, and the “festival days” of the church calendar were painted in understated tones of grey, blue, coral, and gold in a streamlined Art Deco style. They were visually harmonious and easy to read from ground level.

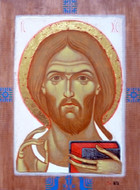

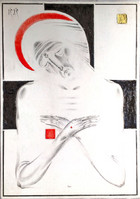

Like many artists in Lviv’s new school of Ukrainian Greek Catholic iconography, Vladyka works in both a traditional and modern style. Looking at two portraits of Christ by Vladyka in the Collection, you would not think they were by the same artist. Ukrainian folk art patterns decorate the frame of his icon of Christ the Ruler of All but the portrait conforms to a 6th century prototype at St. Catherine’s Monastery in Sinai. In contrast, Vladyka’s King of Glory icon presents us with a Shroud of Turin-like photo negative of the body of Christ in a black, red, and white geometric study typical of the Kyiv-born early Modernist Kazimir Malevich.

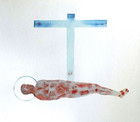

Vladyka experiments with figurative forms in the abstract in his icon of the the Resurrection motif known as the Myrrh-Bearers, using the exposed wood grain as a backdrop. He pushes canonical boundaries to the limits in The Christ of Our Freedom, where Jesus is depicted as a protestor slain in the February 2014 Revolution of Dignity, when massive demonstrations in the capital of Kyiv toppled a corrupt, pro-Russian government. The Holy Face is shielded from tear gas by a blood stained scarf and Christ’s halo is formed from empty bullet cartridges embedded in the kind of wooden panel demonstrators used to shield them from the police.

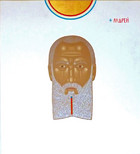

The icons of Danylo Movchan also reflect the modernist aesthetic of Malevich. In his portrait of Ukrainian Greek Catholic Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky, the geometrically composed features of this sacred art patron float on a stark white background. The same feeling for balanced forms in negative space can be seen in Movchan's simply rendered watercolor of the Deposition and his iconographic variation on the motif of the Savior Not Made by Human Hands, based on the time-honored tale of the healing of the King of Edessa by means of a miraculous towel Christ sent with his image. Movchan’s cloth with the Holy Face encircled in blue and gold is meticulously decorated with a three-fold Trinitarian pattern; Christ’s initials appear in paired red boxes. Tetramorph encloses the four symbolic representations of the Gospels in an abstracted cherubic form.

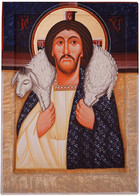

Ivan Dashko studied at the Lviv National Academy of Arts like many artists from the new school of iconography, but he parts company with his contemporaries who experiment with modernist styles to take inspiration from icon-makers of the 15th-16th century, considered to be the golden age of Ukrainian sacred art. Dashko admires “the monumentality” of their technique and their skill in finding “a balance between observing the canons of iconography and improvisation with color,” on view in the vivid blues of the patterned robe and the crimsom-trimmed background curtain in his image of Christ the Good Shepherd.

In Dashko’s icon in the Collection of the Mother of God, a variation on the traditional Byzantine prototype of the Virgin Who Shows the Way, the Lviv artist works in the classical style of Galician iconographers of the golden age. The forms appear rounded, as we see in the face of the Virgin; the garments are painted in bold, contrasting reds, blues and yellows with simple outlines in rhythmic patterns. Says Dashko: “Having such a strong tradition motivates me to spread and develop it.”

A versatile icon-maker who worked in both contemporary and traditional styles in a variety of mediums, Ostap Lozynsky also collected ancient Ukrainian icons and folk art on glass from the Hutsul people of the Carpathian Mountain region, replicated in his reversed glass painting in the Collection of Jesus the Grapevine. Lozynsky could almost always be found at the ICONART Contemporary Sacred Art Gallery in the Armenian quarter of Lviv either helping to mount exhibitions or curating his own shows. His death during the global pandemic was a great loss to the West Ukrainian sacred art community.

Lozynsky updated the traditional format of Eastern Orthodox iconography of the lives of the saints in a two panel painting in my listings of St. Nicholas the Wonder Worker, where we see an abstractly stylized portrait of the popular holy man in horizontal format with visual vignettes of his life and good deeds in an unconventional palette of gray, blue, red, purple, and ocher. He was equally adept in creating holy images on repurposed wood in the style of icons made by village artisans for private devotional use.

The folk art home icon by Lozynsky in the Collection shows a visually-engaging Christ on the Cross between two popular saintly intercessors, George the Dragon Slayer and Nicholas. His version of the Flight into Egypt copies the naïve painting style of self-taught peasant artists who would have understood how important it was for Joseph the Carpenter to take the tools of his trade with him if he hoped to provide for his family in an alien land!

Roman Zilinko also finds inspiration in traditional village icons from Ukraine’s Carpathian region with their naïve, flat painting style, rich in colors and ornaments. While he was working as the Director of Exhibitions at the Andrei Sheptytsky National Museum in Lviv, Roman took me on a tour of its vast icon collection on my first visit to Lviv, pointing out icons of St. George wearing medieval armor in a blending of Eastern and Western art motifs. Schooled in theology, he uses “objects with history” like old wooden boards, panels from chests and doors, and homespun cloth in creating folk art-styled works like The Holy Family and The Christ Not Made by Human Hands in the Collection. Painting with acrylics is his only concession to modernity.

Arsen Bereza, introduced me to more icons made from “found” objects like his rusted Crucifixion scene in the Collection. A richly grained and weathered board serves as the ground for his image of Peter walking on the Sea of Galilee and a rusted bent metal sheet on wood backs a painting of the Good Samaritan. What appear to be decorative markings across the center of a scratched ceramic tile in Crossing the Sea are actually camels, cattle, and human stick figures leaving prints on a path between corroded markings resembling walls of water. This mixed media piece suggests a petroglyph of the Children of Israel crossing the Red Sea that might have been left in the Sinai wilderness by an ancient artist.

Andriy Vynnychok, born in 1967, counts among the elders of the new West Ukrainian school of iconography. He shares a connection with younger icon-makers in the group to the Lviv National Academy of Arts, where he studied in the monumental art department. Vynnychok has covered both church walls and wooden panels with holy images where the defining outlines found in traditional icons often give way to more fluid compositions, molded by contrasting colors and unusual highlighting effects, as we see in his use of red on the lamb held in the arms of his Good Shepherd.

In the icon, Noli me tangere (Touch Me Not), Vynnychok gives a different spin on this time-honored theme of European art, showing the Resurrected Christ’s encounter with Mary Magdalene by the garden tomb. He pays homage to a 1638 painting by Rembrandt, where the Dutch master takes Mary’s initial confusion of Christ with a gardener, quite literally, and depicts the Risen Lord wearing a straw hat with spade in hand. Vynnychok sets his stylized figures in an abstract, broad-brushed background that copies the color palette of the 17th century original.

The last artist in my survey of the Lviv sacred art scene should really take first place, since no one has done more to foster the new school of iconography than Roman Vasylyk. The brother of a Ukrainian Greek Catholic bishop in the underground church, he taught himself iconography and decorated consecrated panels of cloth used in place of altars in clandestine celebrations of the Eucharist. I was fortunate to acquire a piece from Vasylyk for the Collection in a traditional, yet, modern-styled with an image of the Madonna and Child, especially revered by Ukrainian Greek Catholics--the wonder-working icon of the Mother of God of Sambir, a city in the Lviv district near the Polish border.

Vasylyk recognized the coming crisis in the visual arts for Ukrainian Greek Catholics once the church was legalized and set up a six-year study program at the Lviv National Academy of Arts in 1995 to ensure future sacred-art makers mastered traditional painting in tempera on wood as well as other disciplines like encaustic painting; mosaics, stained glass, and iconostasis design. He has shown great breadth of vision in allowing up-and-upcoming icon-makers to pursue their own paths, whether they create images in the 15th century style, icons influenced by village artisans, or contemporary treatments of canonical themes.

Once viewed as the special preserve of Eastern Orthodoxy, icons have made an ecumenical move in recent years into the life and worship of Roman Catholic and Protestant communities with liturgical traditions and have even found a place among Emerging Church groups. The extraordinarily rich and varied iconography of the new Lviv school with its multiple variations in multiple mediums on traditional holy imagery will certainly make this ancient art form even more accessible to larger numbers of Christians—a development in sacred art-making, surely, worth celebrating in the universal church.

Church of the Nativity of the Holy Virgin in Lviv, Ukraine

Interior of the Church of the Nativity of the Holy Virgin, view of dome tower well

Interior of the Church of the Nativity of the Holy Virgin, view of the altar

Sviatoslav Vladyka

Sviatoslav Vladyka

Sviatoslav Vladyka

Sviatoslav Vladyka

Danylo Movchan

Danylo Movchan

Danylo Movchan

Danylo Movchan

Ivan Dashko

Ivan Dashko

Ostap Lozynsky

Ostap Lozynsky

Ostap Lozynsky

Ostap Lozynsky

Roman Zilinko

Roman Zilinko

Arsen Bereza

Arsen Bereza

Arsen Bereza

Arsen Bereza

Andriy Vynnych0k

Andriy Vynnychok