Ethiopian icons

Christianity has a long and venerable history in Ethiopia. The first community of Christians had just been established in Jerusalem, when, according to Acts 8:26-40, the Apostle Philip was sent to witness to “a eunuch of Great authority under Candace queen of the Ethiopians.” In the 4th Century, Christianity was proclaimed the official faith of the Ethiopian Aksumite Kingdom. It became the first nation in the world to use the image of the cross on its coinage.

Elements from Judaism were incorporated into Ethiopian religion in the 13th century, when a new dynasty sought to legitimize its hold on power by claiming lineage from the Hebrew King David through a son of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, named Menelik, who was said to have brought the Ark of the Covenant to Ethiopia. This fusion of Old and New Testament traditions, mixed with elements of Egyptian Coptic, Byzantine, Armenian, Nubian, and European sacred art, has produced a style of iconography unique in Christendom.

Processional crosses like the modern, hand-held version in carved wood with inset icon panels in my collection are an important part of Ethiopian worship. Chapels in a cruciform shape were even cut out of solid rock in Lalibela. But Ethiopia is exceptional among African states in emphasizing painting over three-dimensional art. Ethiopian scribes once excelled at manuscript illumination, but only a few examples of such early liturgical art survived a 16th Century Islamic “iconoclastic” campaign, hidden away in isolated monasteries.

Ethiopia’s sacred art came under threat, again, when a Communist military regime deposed Emperor Haile Selassi in 1974 and tried to suppress the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. The fall of Communism in 1991 has inspired a revival of icon-making, especially among folk artists whose sacred works are presented here in a fascinating variety of styles and media, including paintings on leather and parchment. Images that appear to be the work of the same artist have been grouped together.

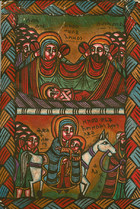

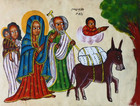

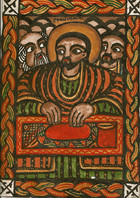

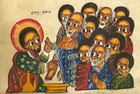

These anonymous artisans work in the styles of the church schools where they train, continuing an art form rooted in ancient illuminated manuscript painting. The Ethiopian icon-makers copy time-honored prototypes but add their own touches. Some paint directly onto the tanned animal hides, while others add elaborate color backgrounds. A few leather paintings strive for traditional representational effects, while other pieces are darkly shaded with expressive distortions of the human form. A distinctive color palette reveals the hand of one artist. Braided frames in various colors signal the work of another icon-maker.

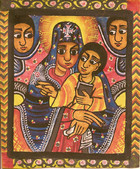

Ethiopian iconography is characterized by vibrant color and repeated decorative motifs, as can be seen in The Virgin Enthroned I on hand-woven cotton gabi cloth, The Virgin Enthroned II on leather, and The Virgin Enthroned III on parchment. Veneration of the Virgin has held a special place in Ethiopian Orthodox worship since a 15th Century emperor ordered she be honored in 30 feast days of the church calendar.

An Enthroned Mary appears, as well, in the second central tier of The Holy Trinity Altarpiece, beneath a representation of the Holy Trinity. This altarpiece is a beautiful example of the Ethiopian style of sequential iconographic story-telling, where various episodes from a sacred narrative--in this case, the Passion of Christ--are presented in a series of related picture panels, somewhat in the style of a holy comic book.

Hand-held Processional Cross (Closed)

Hand-held Processional Cross (open)

The Holy Trinity Altarpiece (Open)

The Holy Trinity Altarpiece (Closed)

The Holy Trinity Altarpiece (Detail)

The Holy Trinity Altarpiece (Detail)

The Holy Trinity Altarpiece (Detail)

The Holy Trinity Altarpiece (detail)

The Holy Trinity Altarpiece (Detail)

The Holy Trinity Altarpiece (Detail)

The Holy Trinity Altarpiece (Detail)

The Crucifixion Altarpiece

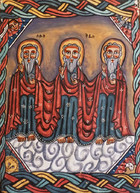

The Holy Trinity I

The Holy Trinity II

The Holy Trinity

The Expulsion from Paradise

The Annunciation I

The Annunciation II

The Virgin Enthroned I

Virgin Enthroned III

The Virgin Enthroned II

The Virgin Enthroned IV

Coronation of the Virgin

Intercession of the Virgin

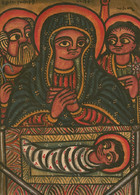

the Nativity I

the Nativity II

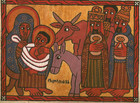

The Adoration of the Magi I

The Three Kings I

The Three Kings II

Presentation in the Temple

Flilght into Egypt

The Nativity and Flight into Egypt

The Flight into Egypt

The Baptism of Christ

Jesus Heals the Blind Man

Jesus Stills the Storm

The Triumphal Entry

The Last Supper

Jesus Washes Peter

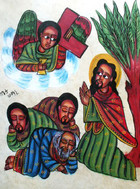

Jesus is Arrested in Gethsemane

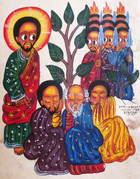

Jesus Prays in Gethsemane

Christ Before Pilate

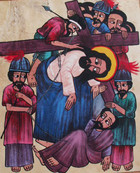

Jesus Stumbles Under the Cross

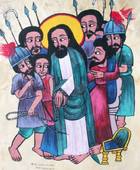

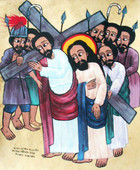

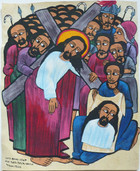

Simon Helps Christ Carry the Cross

Veronica Wipes the Face of Christ

Simon Helps Christ Carry the Cross II

Simon Helps Christ Carry the Cross III

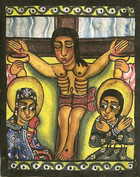

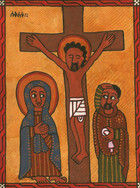

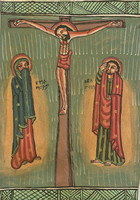

The Crucifixion I

The Crucifixion II

The Crucifixion III

The Crucifixion IV

The Crucifixion V

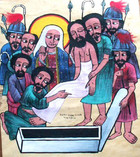

The Entombment of Christ

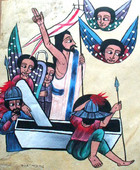

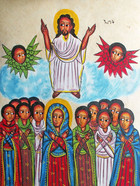

The Resurrection

The Resurrection II

The Resurrection III

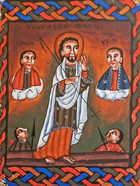

The Ascension of Christ

The Archangel Michael

The Angel Gabriel & the Fiery Furnance I

The Angel Gabriel & the Fiery Furnance II

St. George I