Abraham Rattner

(1893-1978)

Born in Poughkeepsie, New York, Painter and Printmaker Abraham Rattner had no firsthand experience of the rich culture of Eastern European Judaism, which so deeply informed the works of his contemporaries, Marc Chagall and Ben-Zion. Yet, like these two great modern sacred art-makers, he instinctively turned to the stories of the Bible and his Jewish heritage for images, which, he believed, would help him to make sense of a chaotic world, where he felt caught between what he termed “the oppression of reality and utopia.” In intensely expressionist works, Rattner sought to achieve a “symphonic totality and unity,” suggesting “that greater reality of nature created by God and intuitively sensed by man.”

The son of a rabbinical student-turned-baker who had fled Czarist Russia, Rattner encountered anti-Semitic bullying on the mean streets of Poughkeepsie and learned to defend himself, thanks to an Irish policeman who taught him how to box. Rattner’s parents had little money to spare but encouraged their son to pursue his childhood interest in art. He studied architecture and drawing at George Washington University and the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, D.C. Art courses at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia were cut short by America’s entry into World War I in 1918.

Rattner saw frontline action as an officer in a U.S. Army camouflage outfit, where he developed artful ways to conceal artillery. During the second battle of the Marne, he was blown into a foxhole by an exploding shell, suffering a back injury, which troubled him all his life. After the Armistice, Rattner resumed art classes in Philadelphia, then, returned to Europe on a scholarship in 1920. He settled into a studio in Paris, where he would remain for the next twenty years.

The American ex-patriot artist’s sojourn in the French capital coincided with a momentous moment in art history, when Paris was the beating heart of the Modernist movement. Rattner experimented with Futurism, Cubism, and Expressionism; moved in the same artistic circles as Picasso, Braque, Miro and Dali; and formed a lifelong friendship with fellow American abroad, Novelist Henry Miller. As World War II approached, Rattner returned to the U.S with his own fully-formed style of art-making, combining Cubist fragmentation and Expressionist brushwork in works of what he called “poised emotionalism.”

After living two decades abroad, Rattner was appalled at American indifference to the rise of Fascism in Europe. Like Chagall, beginning in the early 1940s, he incorporated imagery of the public humiliation, torture, and crucifixion of Christ into his art to evoke the barbarism of the times and the persecution of the Jews of Europe. As a Jew, Rattner interpreted the Christian Passion narratives in general and personal terms. “It is myself that is on the cross” he explained, “though I am attempting to express a universal theme—man’s inhumanity to man.”

One compelling example of Rattner’s Passion imagery is the 1942 canvas, Darkness Fell over the Land, where the Crucified Christ hangs illuminated above an unholy altar whose base is formed by a frieze of crowned heads, the often sightless rulers of this world who perpetuate violence. A close-up of the Crucifixion crowd reappears in the mixed media print, Among Those Who Stood There, where viewers find themselves viewed as victims—or might it be accessories in crime? Rattner repeated the motif in the 1966 painting, We the People. This time, the by-standers look away in shame and sorrow from a brilliant cruciform figure, suggesting the Resurrected Christ.

In the late 1940s, Rattner turned to Judaism to overcome a spiritual crisis brought on by the sudden death of his first wife, Bettina Bedwell, a fashion journalist whom he had met and married in Paris. As his faith deepened, Rattner came to believe “a painting, if it is achieved at all, is made with the help of God.” As he confessed in a letter to Henry Miller: “I pray every night before I close my eyes; I pray every morning upon opening my eyes, and talk to God and ask for his guidance, direction, clarity, that I may be able to perceive and feel something of that which becomes beauty.” For Rattner, art-making became “a medium of prayer and praise.”

In a portfolio of reproductions, created while Rattner was a visiting professor at the University of Illinois from 1952-1954, almost half the 24 images present biblical themes. There are four studies of the Passion of Christ, an ink wash drawing of Adam and Eve and a collage portrait of a Prophet. Two images depict Job, the universal symbol of suffering. Two more are devoted to Moses, who represented for Rattner “the truth of the oneness of man and God.” Another plate shows the Prophet Ezekiel in the Valley of Dry Bones, an image of particular importance to postwar Jewish artists, who rejoiced in the restoration of a Jewish State in 1948 after the horrors of the Holocaust.

Light and energy flow from God in Judaic mysticism--and light came to play an important role in Rattner’s art in the later years of his life. He chose the theme, And Let There Be Light, for the large stained glass window he created for the Chicago Loop Synagogue in 1958, a vibrantly colored semi-abstract study in sacred symbols, considered to be the most important work of Jewish stained glass in the country. Rattner felt driven, he said, “to let myself into the lighthouse in order to throw the beam of light upon my own inside self and get the excitement of its outward manifestation.”

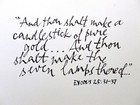

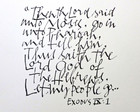

Light figures prominently, as well, in Rattner’s 1972 color lithograph series, In the Beginning, where images are accompanied by biblical texts in the artist’s distinctive calligraphy. Eight of the twelve prints are bathed in light, flames, or fire. Moses and the Burning Bush is the theme of three plates. In a fourth print, Rattner shows the Prophet receiving the Ten Commandments in a firestorm. The creation of light and the separation of day from night feature in two plates, and sacred candelabras and blazing lamps appear in two more prints, Variations for the Menorah and The Shema. As Rattner’s good friend, Miller, wrote in a preface to the portfolio: “His restless, searching heart is united with the anguish of the world and expresses that agony in colors of fire, a purifying fire which nothing can quench.”

Biographical material from Abraham Rattner by Allen Leepa (Harry N. Abrams, New York: 1974)

Darkness Fell Over the Land

Among Those Who Stood There

The Prophets (Three Heads)

We the People

Christ on the Cross

Adam and Eve

Pieta

Study for Job

Job

Crucifixion

Christ Surrounded by Thorns

Head of a Prophet

Moses: Study of the Tablet in Fragments

Moses

The Valley of the Dry Bones

Exodus 25: 31-37

Variations for the Menorah

Exodus 9:1

Moses and the Burning Bush

In the Beginning...

Exodus 3:4

Moses and the Burning Bush

Deuteronomy 6:4-5

The Shema

Genesis 1:3

Let There Be Light

Exodus 3:2

The Bush Was Burning With Fire..

Exodus 34:1