Jean Charlot

(1897-1979)

The term “cosmopolitan” could have been coined to describe Jean Charlot. His father was a Bolshevik sympathizer, born in Russia, the illegitimate son of a French milliner, who received his education in Germany. His mother was a devout Roman Catholic, the child of a Mexican father of French-Aztec ancestry and a mother of Sephardic Jewish descent. Born in Paris, Charlot served as an artillery officer in the French army in World War I. In 1921, he moved with his widowed mother to Mexico, working for a time with Diego Rivera on the Mexican artist's monumental murals, before beginning his own fresco paintings. Charlot was staff artist for three seasons on the archaeological dig at the Mayan ruins of Chichen Itza. He found his way to the U.S., where he taught art in New York, California, Iowa, Georgia and Colorado, finally settling in Honolulu, Hawaii.

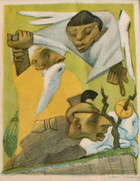

Charlot viewed himself as a “displaced person, partaking of one culture after another,” and his art was strongly influenced by pre-Hispanic Mexican, Hawaiian and Fijian native culture. In Charlot’s view, there were two kinds of art. The vertical, practiced by the Byzantines, El Greco and Eric Gill, and the spherical, made by Giotto, Raphael, and Rubens. Elongated, ethereal shapes had no appeal for Charlot. He preferred “chumming with earth,” like the Aztecs, and loved the molded, mound-like forms of Mexican pottery. Folk imagery of this kind predominates in two sets of lithographic suites, Picture Book (1933) and Picture Book II (1973). Oriental motifs were added to this aesthetic melting pot, when Charlot started working with a sumi brush to create calligraphy-like drawings.

Like Rivera and the radical artists he had come to know in Mexico, Charlot was never really tempted by abstract expressionism, believing art should communicate with viewers. His own message was shaped by his Christian faith and early ties to Guilde Notre Dame, a movement, dating from the First World War, aimed at reforming French Roman Catholic ecclesiastical art. As Charlot once wrote: “One of the threads that binds the epochs of my life, otherwise contrasting and disparate, is love of the liturgical arts.” He believed artists should not have to pray with closed-eyes in order to block out antiquated, irrelevant and downright ugly church decors. His credo: “The best art is none too good for God.”

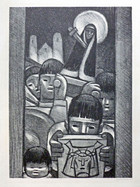

Visiting Hawaii in the winter of 2010, I stopped by the Charlot Collection in the Hamilton Library on the University of Hawaii’s Manoa campus in Honolulu to see the works Curator Bronwen Solyom had gathered together for an exhibition, titled: Image and Word: Jean Charlot and the Way of the Cross. The Stations of the Cross preoccupied Charlot all of his life, and Bron had an impressive display to show me, everything from woodcuts from 1918-1920 in an Art Nouveau-Art Deco style to photographs of minimalist images Charlot imprinted with styrofoam molds into concrete wall niches for a parish in Hawaii in 1971. (There is one Charlot lithograph in the Sacred Art pilgrim collection, First Fall: Station III, from an unfinished Stations of the Cross series, dating from 1948.)

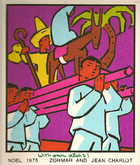

Charlot was as versatile an artist as he was well-traveled. He produced oil paintings on canvas, acrylics on panel, woodcuts, lithographs; murals in fresco, mosaic and ceramic tile; sculptures, and numerous book illustrations, like the simple but sensitive images he made in his neo-Aztec style for the children’s book, Martin de Porres, Hero. I must confess, my favorite Charlot illustrations are his macabre sumi-pen drawings and captions for Dance of Death, his homage to Mexican Print-Maker Jose Posada, a true master of the subject. Charlot was a gifted cartoonist, whose work frequently appeared in Catholic publications. He described his faith with humility as “the religion of the parishioner.” Not all artists have this gift for keeping life in a perspective. For Charlot, creating fine art Christmas cards for family and friends was no less important than monumental art commissions.

Self Portrait

First Fall: Station III

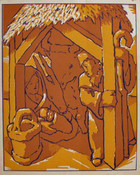

The Nativity

The Nativity (1977)

The Sacrifice of Isaac (Plate X)

Raising of Lazarus (Plate XIX)

Terracotta (Plate I)

The Good Shepherd (Plate XXX)

The Holy Family (Plate XXXII)

Martin de Porres, Hero (Book Jacket)

Chapter: Mr. Unknown

Chapter: The Thrill of Learning

Chapter: Boys' & Girls' Friend

Dance of Death (Frontispiece)

Death and the King

Death and the Hermit

Death and the Artist

Cartoons Catholic (Book Cover)

Christmas Week

St. Joseph (March 19, May 1)

Feast of Christ the King

Christmas 1954

Christmas 1974