Edward Knippers

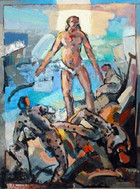

Edward Knippers gives new meaning to the term figurative art. Enter his studio in Northern Virginia, and you might think for a moment you were in the Sistine Chapel. Stacked in two tiers along the wall are oil-painted panels of enormous size, teeming with characters from the Bible, standing, sitting, walking, running, striking blows, warding them off, hunched over in despair, fallen back in ecstasy, soaring heavenward, plummeting to earth--and all of them, gloriously nude. “Glorious,” because Knippers happens to believe “the body is an essential element in the Christian doctrines of Creation, Incarnation and Resurrection”--and, therefore, the central theme of his sacred art.

Although Knippers studied under two leading abstractionists, William Stanley Hayter and Zao Wou Ki, he began to question modernist notions about representational art, when he viewed a rare exhibition of the works of Caravaggio. His real “conversion” to figurative painting came at a performance of George Balanchine’s ballet, The Prodigal Son, with set designs by Georges Rouault. Knippers was watching the dancer in the title role crawl across the stage on his long journey home, when he realized the immense emotive power of the human body in expressing spiritual themes.

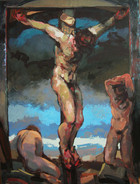

Knipper’s art defies labeling. A superb colorist who knows the works of the Baroque masters as well as Matisse and Cezanne, he is equally at home, making monochrome prints, like his lithograph, The Crucifixion, which vibrates with a visual energy, recalling the German Expressionists. The dynamic abstract patterns in his woodcut of The Good Samaritan suggest the work of his mentor, W. S. Hayter. Knippers also incorporates “Cubist” elements in his paintings to depict moments in the Bible narratives when the supernatural intrudes into the natural world.

Bible stories like the saga of Joseph and his brothers and the Passion of Christ continue to be the central theme of Knipper's art, but following in the footsteps of his mentor, Rouault, he recently began a series of paintings about circus performers, whose daring aerial feats represent, for him, a search for “false transcendence.”

Knipper’s unabashedly sacred subject matter may not be to the taste of secular post-modernists and his unashamedly nude figures may shock many church-goers, but none of this phases Knippers. His passionate commitment to a specific visual ideal has produced a body of work unique in contemporary sacred art.

Joseph in the Pit

Joseph Sold into Slavery

Christ and the Demoniac

Christ Among the Lepers

Christ & the Money Changers

Christ Mocked by a Dwarf

The Crucifixion

The Supper at Emmaus

Circus Performers: Study I

Circus Performers: Study II

Circus Performers: Study III

The Good Samaritan

The Good Samaritan