Frank Humphrey Allen

(1896-1977)

Sacred art can be found in the most unexpected places. I discovered Frank Humphrey Allen’s work at a sales exhibition in a resort hotel at Coral Bay on the island of Cyprus. One look at his imaginative, idiosyncratic paintings told me they would find no buyers in a tourist venue. My hunch about the quality of the artwork was confirmed, when I heard the artist's life story from his niece. During the 1930s and 1940s, the London-born Allen studied his craft and took part in exhibitions alongside artists whose names now read like a Who’s Who of Contemporary British Art. Then, in 1949, he abandoned the London art scene to lead a quiet life in Norfolk. He died unrecognized by the British art establishment, leaving behind a treasure trove of unknown works.

Beginning artists often experiment with different styles and media, appropriating what they like from other artmakers. Those who are market-minded eventually evolve a distinctive style, which makes their work readily identifiable to collectors. See a blue dog and you think of Cajun Artist George Rodrigue. Forms turned upside down bring to mind German Painter Georg Baselitz. Allen refused to become a “niche” artist with a trademark style and considered artmaking a school of continuing education. In his Norwich row house, the reclusive artist avidly followed BBC Radio cultural news and collected exhibition catalogs and monographs on popular period artists. When English Artist Graham Sutherland was creating "organic" grotesques, Allen made tree monsters of his own. Russian Modernist Wassily Kandinsky's biomorphic studies inspired an Allen series of floating abstracts.

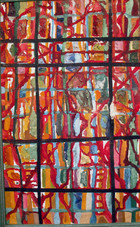

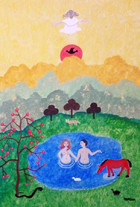

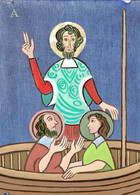

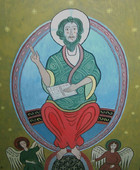

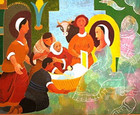

Religious themes appear frequently in Allen’s art in an astonishing range of styles, as can be seen in his works in the Sacred Art Pilgrim Collection. Biblical Landscapes I, Biblical Landscape II, The King, and Stained Glass Study show the influence of French Sacred Artist Georges Rouault and his stained-glass-modeled imagery. There are touches of Swiss Artist Paul Klee in Tobias & the Angel, a childlike sacred scene where angels beckon and dogs romp. Garden of Gethsemane suggests a Klee dream landscape of more enigmatic meaning. Allen was not only interested in the Modernists. His naïf gouache paintings, The Call and Light of the World, recall medieval illuminated manuscripts. while Sacred Conversation is a modern variation on a popular 15th century genre of Italian sacred art.

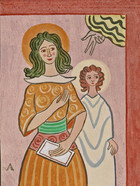

The Annunciation is the subject of three very different pieces in my collection. Annunciation I looks like a Cubist study for a stained glass window, where the Virgin Mary turns away in surprise from a wingless Gabriel, viewed in profile in the style of the Annunciation angels of Medieval and Renaissance art. Annunciation II shows a thoroughly modern Mary with a book (or, perhaps, a heavenly express mail letter) in her hand. The angelic figure in the background has been upstaged by the Hand of God, extended from a cloud, a traditional way in early Christian iconography of depicting God the Father. In Annunciation III, Allen returns to the dream landscapes of Klee, setting the scene amid exotic flora and fauna, suggesting Paradise Lost and the Virgin Mary's role as the New Eve, whose obedience to God makes right the wrong committed by the First Eve in the Garden of Eden

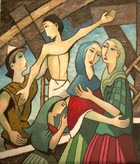

Allen's unusual use of conventional religious imagery often uncovers new levels of meaning. In The Crucifixion, Allen shows the youthful, beardless Christ of Early Christian art on the way to Golgotha, inspiring reflection on Jesus as the innocent Lamb of God and Only-Begotten Son. In the Studio, a curious interior scene of paintings within paintings, Allen turns the objects in an artist's work space into numinous symbols. A trinity of fish swim in an aquarium. An angelic figure looks out from a picture, propped up on an easel, ressembling a cross. Allen is one of the most appealing contemporary exponents of the endangered tradition of artistic storytelling, an all but forgotten artist who deserves to be accorded his proper place in 20th century art—whether sacred or secular.

Biblical Landscape I

Biblical Landscape II

The King

Stained Glass Study

Tobias & the Angel

Two Blessed

Garden of Gethesmane

The Call

Light of the World

Sacred Conversation

Annunciation I

Annunciation II

Annunciation III

The Nativity

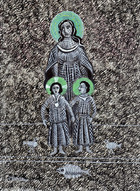

The Virgin Mary, Jesus, and John the Baptist

The Crucifixion