Benton Spruance

(1904-1967)

American Artist Benton Spruance is, without question, the lithographer’s lithographer. Spruance’s eyes were first opened to the expressive power of this print medium, when he saw lithographic studies of gritty urban life by Ashcan School Realist George Bellows at a memorial exhibition for the artist in 1925.

An art scholarship took the Philadelphia-born Spruance to Paris three years later, and while looking for art supplies one day, he discovered the workshop of French Master Printer Edmond Desjobert. What had been a passing interest in lithography soon blossomed into a life-long passion.

The Atelier Desjobert was a gathering place for American ex-patriot artists in 1920s Paris with an interest in lithographic print-making. Spruance found he loved everything about the process from the smell of the ink to the feel of the grease crayons, making patterns on the limestone printing surface. He returned to the U.S. determined to make his mark--on lithographic slabs.

The commercial development of off-set lithographic printing had all but supplanted stone print-making in the U.S. by the 1930s, but Spruance was fortunate enough to meet Theodore Cuno, a German immigrant living in North Philadelphia with an old lithographic press in his basement. To support his wife and two sons, Spruance taught art at Philadelphia’s Beaver College and the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art (now the College of Art and Design), getting his hands spattered with printer's ink at every opportunity.

Spruance’s partnership with Cuno would last for over twenty years, until Spruance began producing stone-made prints on his own, so he could experiment with new types of color lithography. He pioneered a special “subtractive” process for making multicolored prints from a single slab (instead of using several) simply by reducing the area of the print surface on the stone as each new color was added.

Like his mentor Bellows, Spruance won early fame for his sporting prints, showing shadowed, sinuously contoured football players in motion. During the 1940s, the lithographer turned to weightier subjects, influenced by French Print-Maker Georges Rouault, whose religious-themed works he much admired. Spruance was a nominal Episcopalian with no great love of organized religion but he was drawn to the great biblical narratives.

Spruance often set Bible stories in modern settings to comment on contemporary issues or to illustrate events in his own life. Sometimes sacred subjects simply provided a visual language to interpret universal themes like the human struggle with evil. Said Spruance: “I’m one of those peculiar artists who likes to go back to the Bible for inspiration again and again, not necessarily because of the religious content but because of the universal content.” Spruance’s style became more abstract in later years, but the preoccupation with biblical themes remains unchanged.

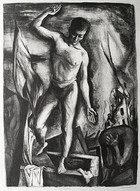

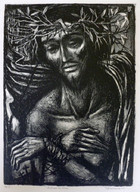

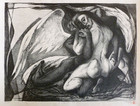

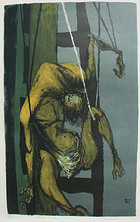

The lithographs by Spruance in the Sacred Art Collection reflect this artistic evolution. Pieta-From the Sea (1943), Resurrection (1944), Behold the Man (1947), Havoc in Heaven (1948), and Jacob and the Angel (1952) display a stylized realism, much like the work of Bellows and American Regionalist Artist Thomas Hart Benton. Two Angels (1955) and Black Friday (1958) in both black and white and color versions show increasing distortion of form and jagged, expressive line work. Galilee (1961) and Tobias & the Angel (1967) are constructed, largely, from abstract shapes with clear figurative elements. Spruance never wanted to lose meaning in his experiments with modernist forms.

Biographical material from Benton Spruance: The Artist and the Man by Lloyd M. Abernethy (Associated University Presses, Inc.:1988)