Bernard Brussel-Smith

(1914-1989)

Bernard Brussel-Smith can claim a place at the top of the list of American artists who have excelled at wood engraving. Studio courses in oil painting and more conventional media at the Pennsylvania Academy of Arts held little appeal for Brussel-Smith. The Greenwich Village-born artist discovered his true talent, working with Wood Engraver Fritz Eichenberg at the New School in New York City. Brussel-Smith showed such promise after only one year of study in this most exacting form of print-making that Eichenberg asked him to be assistant instructor of the class. He would work almost exclusively in wood engraving until his death close to fifty years later.

Wood engraving is a cerebral art form, where texture and tone must be carefully created by lines of varying length and width carved into an end grain piece of wood and not by the vagaries of brush work or sketching. These restraints suited Brussel-Smith, and he expanded the use of wood engraving beyond editorial art into advertising. He not only published illustrations for the folk song collection, Sing of America (1947), and for periodicals like Time, The Saturday Evening Post, and Reader’s Digest, but also created commercial designs for Smith, Kline, & French and Seagram. Brussel-Smith taught art, as well, at the Brooklyn Museum, Cooper Union, and the National Academy.

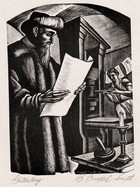

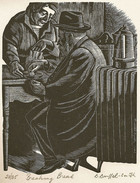

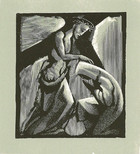

Brussel-Smith was concerned with social issues and the life of the urban working class, often incorporating religious themes into this works. In Breaking Bread (1942), an early engraving in the style of his mentor, Eichenberg, a shared meal becomes a solemn rite for an aging Orthodox Jewish couple. The image of the bearded prophet, seen in Moses and The Ten Commandments (1956), became a personal motif for Brussel-Smith and dominated his Danse Macabre series of the 1970s, where he depicted his return to life after two near-fatal bouts of illness.

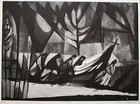

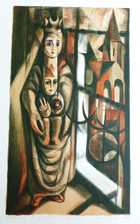

Brussel-Smith spent summers with his family in Collonges-la-Rouge, a village in South Central France, recording scenes of rural faith like the funeral procession in Cortege (1967).The color woodcut, Apostles, resembles a figure grouping on the 12th century carved stone tympanum of the village church, which can be seen through the window in the color lithograph, Statue of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child. The sculpture of the Madonna and Child in this print recalls medieval French woodcarvings in an iconographic style known by the Latin term, Sedes Sapientiae, Seat (or Throne) of Wisdom, a term of devotion for the Virgin Mary.

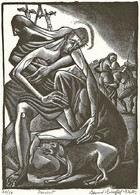

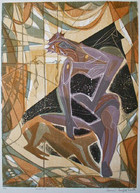

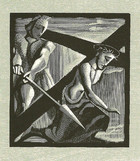

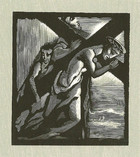

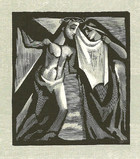

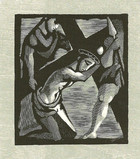

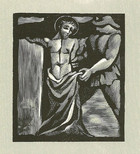

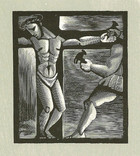

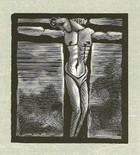

Brussel-Smith was especially drawn to the Passion of Christ, creating harrowing and poignant images like Descent (1948), where a dog licks the nail wounds in the feet of the dead Jesus, recalling the parable of Lazarus and the Rich Man in Luke 16:19-31. He took up the theme again in the more abstract Descent II (1965/1981), printed in a special color relief process, inspired by the works of English Poet-Artist William Blake. In the mid 1960s, Brussel-Smith spent over two years contemplating and developing a cycle of chiaroscuro, small-format Stations of the Cross woodcut/wood engravings.

The Master Print-Maker talked about the project in the April 1966 issue of American Artist: “In Christianity, all life revolves around Jesus Christ. His story is the simple, forthright story of Man: Man in his suffering, anguish, love, hatred, compassion, fear, and every other basic condition of life on earth: Man, the perpetrator as well as the receiver of justice and injustice; Man, the hunter as well as the hunted. Hatred and love, good and evil live side by side, and the vessel that harbors these characteristics is Man. Because these emotions are so fundamental, even the lowliest can grasp their meaning. For me, the message is a vivid experience.”