John Mosiman

(1931-2012)

American Graphic Artist John Mosiman’s work comes out of a sacred art tradition I know well from my childhood years in a conservative Baptist faith community in the late 1950s: the chalk art ministry. There were almost no religious images on display where we worshipped, so, it was a rare treat to be visited by a guest speaker, skilled in this visual tool for evangelization, whose best-known practitioners include Warner Sallman, Phil Saint, and Esther Frye.

As you watched spellbound from your pew, these itinerant artist-preachers used their easels as pulpits, illustrating a gospel message in chalk sketches, drawn with lightning speed on sheets of specially prepared paper. In a dazzling final touch, they would often flick on a black light to reveal the Cross or, perhaps, the face of Christ, shining through the outer drawing. If you were lucky, you might even be the one chosen to take the precious chalk sketch home with you.

Born in Elgin, Illinois, Mosiman graduated with an arts degree in 1953 from nearby Wheaton College, a center of American Evangelical Protestantism, where he learned chalk drawing from W. Karl Steele, a pioneer in black-light chalk effects. After taking graduate courses in printmaking at Northern Illinois University, Mosiman joined the staff of the missionary radio station, HCJB (Heralding Christ Jesus’ Blessings), in Quito, Ecuador.

During his time in Latin America, Mosiman put his artistic skills to good use in a chalk art ministry at evangelistic tent meetings. Local audiences marveled at these impromptu works by a left-handed artist, wondering what masterpieces Mosiman might have created had he been right-handed!

After 12 years of missionary service, Mosiman returned to the U.S. and took up peformance art, staging “musical painting” demonstrations for schools, civic and religious groups, criss-crossing the country, as well Canada and seven Latin American countries.

Mosiman would set up a large easel on an illuminated stage and create pictures, inspired by musical compositions like Ferde Grofe’s Grand Canyon Suite. He synchronized his mark-making in time with the music in a melding of sound and movement, which viewers compared to ballet choreography. Mosiman created screen-made prints to sell as souvenirs of his musical events.

In his free time, Mosiman carved Bible verses onto walking sticks and managed to climb 47 peaks in the Rocky Mountains. He eventually retired to Austin, Texas, where he devoted the last years of his life to sponsoring Mexican students for higher education and helping to build as many as 150 homes for destitute families across the border.

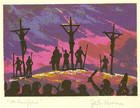

In his "performance art" appearances, Mosiman perfected a spare style of image-making, which allowed him to replicate biblical motifs in expressive ways with an economy of means. The same bold use of color and simplicity of form apprears in the serigraphs now in the Sacred Art Collection, based on these "live" creations.

Three pairs of prints on the Parables on view here show his skill in working with themes and variations. The glowing purple, reddish pink background of The Manger Scene and The Crucifixion with its touches of gold bring to mind the brilliant, black light special effects summoned up by the artist-evangelists of my youth in the grand finale of their chalk sermons.