The Family Lorenzo

Halfway between Mexico City and the resort of Acapulco, Mexican Federal Highway 95 passes through the town of Xalitla on its way south through Buzzard Canyon and across the Rio Balsas toward the Pacific seacoast. Many of the inhabitants of this community in the mountainous interior of the Southern Mexican state of Guerrero are from the Nahua people, whose handicraft items find ready buyers in the folk art markets of Mexico City and the Acapulco gold coast. Life there is far from idyllic. Drugs also move between these two urban centers. Four victims of a gangland-style execution were found in the center of Xalitla in 2011 with warning signs from narco-business bosses.

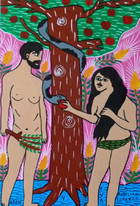

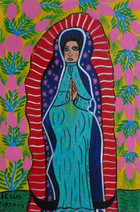

The region around Xalitla has traditionally been famous for its hand painted ceramics. In the early 1960s, local artisans transferred their brightly-colored designs from clay to more easily transportable amate paper, the Mesoamerican equivalent of papyrus, pounded out of pithy tree bark. One painter in Zalitla who learned his craft working on this sacred paper of the Aztecs was Lucas Lorenzo. He eventually switched to painting on masonite panels, using the same brilliant colors and stylized motifs of amate paper imagery to create his own distinctive brand of folk art.

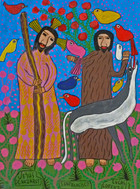

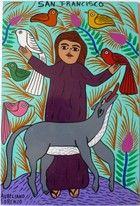

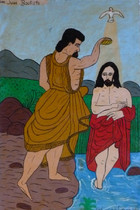

As often happens in rural artisan communities, once the senior Lorenzo found a market for his striking masonite panel art pieces, other family members joined in. Lucas’ four sons, Aureliano, Jesus, Nicolas, and Santiago, are now panel painters, as well as his two daughters, Carlota and Socorro. The family art franchise will, no doubt, pass to a third generation. The Lorenzo offspring mostly work in the same naif style as father, Lucas, adding a few more realistic touches suggestive of traditional sacred art, as can be seen, when comparing father and son renditions of the Baptism of Christ in the Sacred Art Pilgrim Collection.

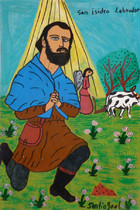

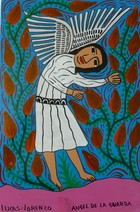

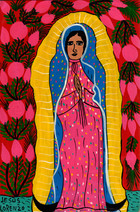

In these high-gloss masonite art pieces, we get a glimpse of heaven and earth, as seen through the eyes of Mexican villagers, who consider Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the saints to be powerful intercessors in the their daily lives. St. Anthony the Abbot (the Desert Father) appears in a field with farm animals in his role as a protector of livestock. St. Pascual Bailon, the patron saint of chefs and cooks, has a vision of the holy food of the Eucharist among the pots and pans of the kitchen. St. Patrick from the Emerald Isle shows up to do a bit of snake maintenance work, while an angel plows the field to give St. Isidore the Farmer time for prayer.

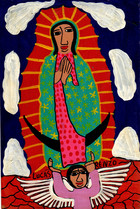

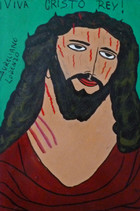

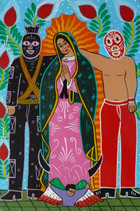

Local color and topical references abound in these sacred art pieces. The Three Kings travel on exotic spotted beasts under a blazing sun across the ruggedly green terrain of the Guerrero region. A jaguar, the sacred totem of the Mayans and Aztecs, takes pride of place among the animals gathered at Noah‘s Ark, while Our Lady of Guadalupe looks on. In another delightful panel, Mexico's beloved Patron keeps company with two heroes of popular culture: a lucha libre wrestler and a black-masked, "freedom-fighter" from the Zapatista National Liberation Army. The phrase, Viva Cristo Rey ("Long Live Christ the King!"), painted on a portrait of Christ, recalls the rallying cry of peasant rebels in a 1920s uprising against an anti-clerical, revolutionary regime in Mexico City.

Lucas Lorenzo

Lucas Lorenzo

Lucas Lorenzo

Lucas Lorenzo

Lucas Lorenzo

Lucas Lorenzo

Lucas Lorenzo

Lucas Lorenzo

Lucas Lorenzo

Lucas Lorenzo

Lucas Lorenzo

Lucas Lorenzo

Lucas Lorenzo

Aureliano Lorenzo

Aureliano Lorenzo

Aureliano Lorenzo

Aureliano Lorenzo

Aureliano Lorenzo

Carlota Lorenzo

Carlota Lorenzo

Jesus Lorenzo

Jesus Lorenzo

Jesus Lorenzo

Jesus Lorenzo

Jesus Lorenzo

Jesus Lorenzo

Nicolas Lorenzo

Santiago Lorenzo

Santiago Lorenzo