Harry Anderson

(1906-1996)

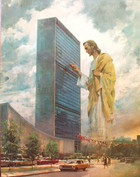

If you had asked me a few years back to choose one painting, epitomizing what I most disliked about contemporary “Christian Art,” it would, no doubt, have been Prince of Peace by Harry Anderson. The idea of a gigantic Christ seeking entrance to the United Nations Secretariat, in imitation of Pre-Raphaelite Artist William Holman Hunt’s iconic painting, The Light of the World, might, possibly, have worked had it been attempted in a surrealistic or expressionistic style. But the realistic detail in this bizarre picture overwhelms the viewer, evoking absurd images of a Godzilla-like Jesus on a rampage through Manhattan, his mighty fist, shattering glass and twisting steel, his awesome feet, reducing the fleeing Yellow Cab to smithereens!

As I grow older (and less categorical in my views on art!) the works of Harry Anderson and his near contemporary, Warner Sallman, hold greater appeal for me. I am always glad to find their images, which were largely created for a mass audience, in vintage print reproductions. They are honest in conception and sincere in purpose, displaying a technical expertise, common to a generation of American artists (including Edward Hopper) who learned their trade, illustrating American periodicals like Collier’s, the Ladies’ Home Journal or the Saturday Evening Post. Anderson and Sallman were both men of faith who saw no contradiction in using a style of art, associated with their commercial work in advertising, to promote the Christian message.

I’m especially fond of Anderson’s What Happened to Your Hand?, found in an Ohio flea market. This image and Jesus, the Friend of Children bring back memories of elementary school reading books with Dick and Jane and the illustrated Sunday School newspapers of the 1950s. Such studies of Jesus in flowing, white robes with children in contemporary dress may be judged a bit too saccharine by today’s sardonic standards, but the mix of the ancient and modern in What Happened to Your Hand? was considered quite audacious, when it first appeared in a Seventh-day Adventist Church children’s publication in 1945.

There is, in fact, a venerable tradition in sacred art of depicting the characters of biblical stories in contemporary settings and dress. Consider, for example, Caravaggio’s magnificent oil painting, The Calling of Saint Matthew, which takes place in a 16th Century Roman tavern. Anderson, no doubt, drew direct inspiration for his own, distinctly American brand of "supernatural realism" from widely-circulated reproductions of popular 19th century works like French Realist Leon-Auguste L’hermitte’s Friend of the Lowly and German Fritz von Uhde’s Come, Jesus, Be Our Guest.

Anderson's Jesus for a modern age is big enough to embrace a great metropolis in Christ of the City and humble enough to make a hospital call in The Consultation. As Anderson once put it: “This is the way, if I met Him, I’d like to see Him.” Hopefully, not looming large outside the U.N.!