Bohuslav Reynek

(1892-1971)

One biographer of Bohuslav Reynek presents the chapters in his life story as the fourteen Stations of the Cross. The devotional metaphor is appropriate for this Czech artist of faith. Considered to be one of the most important poet-artists to come out of Bohemia in the modern era, Reynek lived through two World Wars, the coming of Communism to Czechoslovakia, and the brief period of freedom, known as the Prague Spring, dying shortly after the restoration of a Moscow-controlled regime. Reynek saw his family manor house taken from him twice and spent the last quarter century of his life as a state worker on his own land, tending sheep and goats by day, making exquisitely-detailed graphic images at night by candlelight--an artistic and spiritual climb up Golgotha.

Reynek was the only son of an estate owner in Petrkov in Eastern Bohemia and was educated in a German school, where he mastered both German and French. His father wanted him to study agriculture in Prague, but he left after a few weeks. Reynek was a poet, at heart, with a talent for drawing. In 1914, he met Josef Florian, a visionary Roman Catholic publisher. During their fruitful period of collaboration, Florian printed Reynek’s poems and his Czech translations of French and German writers, including works by leading French Catholic poets and intellectuals like Paul Claudel, Charles Peguy, and Leon Bloy, whose radical Christian writings also influenced French Artist Georges Rouault.

The shy poet-translator was so impressed by the verse of French Writer Suzanne Renaud he went to visit her in Grenoble. They were married in 1926. Reynek settled for a time in France, where he devoted himself to drawing landscapes and sacred architecture, displaying his artwork for the first time in a Grenoble gallery in 1927. Two sons, Daniel and Jiri, were born to the couple. Reynek and his family spent their winters in Grenoble and summers in Bohemia. When Reynek’s father died in 1936, the artist-poet inherited the family estate in Petrkov. He fixed up the manor house, moved in permanently with Suzanne and his two sons, acquired a flock of sheep, and found inspiration for his poetry and art in the surrounding countryside and the daily routine of the farm.

This idyllic life came to an end during World War II, when Nazi occupation forces took over the Petrkov estate. The Reynek family moved in with the children of Publisher Florian. After the war, they returned to the manor house, where the poet-artist resumed his life of shepherding and independent art-making until 1949, when the new Communist regime began nationalizing private property and turned the Reynek homestead into a state farm. Bureaucratic incompetence and the timely intervention of friends saved the family from outright eviction. Reynek was no longer allowed to travel abroad, and his poetry and art were suppressed by official censors, who found his work to be too religious.

Reynek assumed the life of a poet-prophet without honor in his own country, finding solace in his faith, his family, his art-making, and his hours spent among the sheep and goats of the state farm. In the years leading up to the Prague Spring of 1968, when the country’s leaders tried to create “Communism with a human face,” Reynek’s retreat from the world was disturbed in an unexpected way. He had turned into something of a cult figure for younger Czech poets and artists, who came on pilgrimage to Petrkov. For a time, his poetry reappeared in print, and his art was displayed in galleries across the country. After the Soviet-led Warsaw Pact invasion in August 1968 crushed the Czechoslovak reform movement, Reynek found himself once more in spiritual exile.

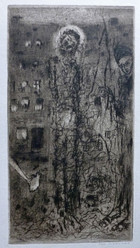

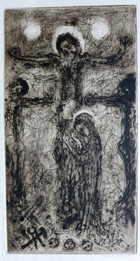

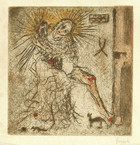

From 1933 until his death in 1971, Reynek produced over 600 works of graphic art on a hand press at the Petrkov manor house with help from his sons. He had experimented with linocuts in the early 1920s, working in the simplified style of his artist friend, Josef Capek, who illustrated Reynek’s 1922 collection of prose-poems, Fish Scales. In 1933, using a manual on print-making as a guide, Reynek taught himself to make drypoint prints. He found he was able to create delicate images with webs of gossamer-like lines by pressing a hard-pointed “needle” directly into the metal printing plates. In 1946, Reynek added color to his graphic images by making impressions from his drypoint plates onto hand-colored monotype sheets. He added final color accents with wood slivers, turning each piece into an original work of art.

Given the troubled times he lived in, Reynek manages to infuse his sacred subjects with an extraordinary sense of serenity and compassion, evident in one early linocut print in the Sacred Art Pilgrim Collection, Beloved of the Lord, where Jesus tenderly offers the Eucharistic elements to a lone disciple. In Stabat Mater II, our eyes are immediately drawn to the deeply inclined heads of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the Repentant Thief, an iconographic pose, repeated three times, which unites the suffering figures in their grief, resignation, and love. Even in Reynek’s depiction of The Flagellation of Christ, the brutality of the subject is softened by a hand extended from the lower left, offering a jug of water.

Reynek’s graphic works present the world through the eyes of a contemplative, who sees divine intimations in everyday things and encounters Christ and the saints on the stairwell and in the front yard. In Veronica with Christ II, the woman who wiped the face of Jesus on his way to Golgotha discovers his image on her veil, standing beside a window with a potted plant. In Pieta with Mouse, the robes of the Virgin Mary provide refuge for a mouse, as she cradles the body of her son in her arms near a house door. The Apostle Peter stares in wonder at a fish, perhaps, the one caught at Christ's command with a coin in its mouth for the temple tax or in the miraculous draught of fishes

A passage from Reynek’s prose poem, “Landscape,“ in Fish Scales beautifully expresses his mystical view of life: “Angels of solace, embroider a picture in the spring gosssamer for us, who are confused and whose teeth are chattering. Fill us with the undiminishing manna of beauty.”

Biographical material taken from Bohuslav Reynek: Mezi nebem i zemi by Pavel Chalupa (Arbor vitae: 2011). Poetry quotation taken from Fish Scales by Bohuslav Reynek, translated by Kelly Miller and Zdenka Brodska (Michigan Slavic Publications, Ann Arbor: 2001).