Nativity Sets and Scenes

St. Francis of Assisi can take credit for creating the first Nativity scene. As his biographer, St. Bonaventure, tells the tale, Francis was looking for a way in 1223 to make the Christmas story more accessible to the villagers of the Italian town of Greccio and decided to set up his own simple manger. With the blessing of the Pope, he brought hay, an ox, and an ass to a niche in a rock and gathered the faithful for Midnight Mass, calling on them to behold the crib of the “Babe of Bethlehem,” their king so humbly born. St. Bonaventure reports some spectators did see “an infant marvelously beautiful, sleeping in the manger.” The leftover hay “miraculously cured all diseases of cattle, and many other pestilences.”

Francis’ novel nativity set piece quickly caught on across Europe. In an age of mystery and miracle plays, performers appeared as the Holy Family, the Shepherds, and the Wise Men. Never mind they could not all have been in the same place at the same time, as biblical scholars are quick to point out! Figurines soon stood in for people in Christmas displays. The first such crèche (from the French word “crib”) was a marble statue group Tuscan Sculptor Arnolfo di Cambio carved in around 1290 to go with what were believed to be boards from the Bethlehem manger in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome. Some of the figures can still be found in a crypt chapel of the church.

The golden age of crèche-creation came in 18th century Naples, when artisans moved the manger scene from Bethlehem into bustling towns of their time, expanding the traditional biblical cast with dozens of miniature terracotta figures of butchers and beggars, fops and fortune-tellers, principesse and priests, decked in silks and satins and buckles and beads. Charles III, King of the Two Sicilies, was said to have owned more than 6,000 Nativity figures, inspiring a crèche-collecting craze throughout his kingdoms and beyond. Sumptuous examples of Neapolitan presepe (a variation of the Latin word for “manger”) have gone on seasonal display at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, the Chicago Art Institute, and the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh.

Creches in all shapes and sizes remain as popular as ever in the post-modern era with Friends of the Creche societies, crechemania websites, and seasonal European crèche tours. One “must” stop for any manger-maven is Sao Paio de Oleiros in northern Portugal, which holds the Guinness World Record for the most mechanical figures in a nativity scene. There are over 160 to be found among 7,000 figurines in a 2000 square meter area interconnected by 50 km. of electric cables. Typical exhibits include a life-sized Pope Francis bowing his head to receive a blessing from the moving hands of Our Lady of Fatima; Joseph wielding a hammer and chisel in his workshop; and Mary adjusting the swaddling clothes around the Baby Jesus.

Creches can sometimes be cause for controversy. Church leaders criticized London’s Madame Tussards museum for going too far in a 2004 waxwork celebrity display featuring Football Star David Beckham and his Spice Girls spouse, Victoria, as Mary and Joseph. When local officials in the Catalan capital of Barcelona recommended removing the traditional comic figure of El Caganer (The Pooper) from public nativity scenes in 2005 to discourage people from relieving themselves on city streets, the outcry was so great he was kept in place. In the U.S., legal challenges to Nativity sets on public property continue with many communities following the “reindeer rule” of more “inclusive” seasonal displays.

The only strong feeling the nativity scenes and sets on display here should arouse is one of delight at things cleverly conceived and beautifully made. The global advance of Christianity has taken the Nativity scene from its small-town Italian origins out into the big wide world. International potters, painters, woodcarvers, and weavers offer new variations on standard “Western” crèche prototypes, reflecting their own cultural heritage.

Camordino Mustafa Jetha ("Dino"), a woodcarver from Mozambique, has fashioned a Christmas display from cashew nut wood, Nativity in Tete, a west-central region of the country, where a hollowed out baobab tree serves as a manger for the Holy Family. Two speckled cows keep watch at this unusual stable, while a dog-walker, a child with a water pot, and a woman carrying chickens to market go about their daily lives. In a blackened-clay pottery Nativity scene from Cameroon, the Christ Child’s visitors wear traditional aso oke and kufi hats, and a short-horned Brahman cow takes the place of the ox at the manger. Thai Potter Duangkamol Srisukri has created a Nativity scene in traditional Celadon (green stone) glazed ceramics, highly prized for its resemblance to jade. A deva, a celestial being in Buddhism, and a water buffalo keep watch over the Baby Jesus.

Chinese artisans at the Dongyang Christian Woodcarving Factory in the coastal province of Zhejiang carry on a folk art tradition dating back some 1,300 years to the Tang Dynasty in their hand-crafted Christmas displays. The workshop is the only one of its kind in China, founded by Master Woodcarver Zhang Wan Long, who designs the religious-themed pieces. The folding bas-relief Nativity triptych in the collection takes the form of ancient city gates. A water buffalo and lambs appear with the Holy Family in the central panel. To the right, an angel announces Christ's birth to the Shepherds; to the left, the Wise Men travel on camels to Bethlehem. The Christmas Star illuminates all three scenes. The Chinese inscription on the two central pillars quotes Isaiah 9:2 (KJV): "The people that walked in darkness have seen a great light: they that dwell in the land of the shadow of death, upon them hath the light shined."

In Varanasi (also known as Benares), the holiest of Hinduism’s seven sacred cities, Indian artisans make Christian Nativity scenes in the same style as the brightly-colored wooden toy figures of Hindu gods and goddesses, birds, and animals, which are much-loved souvenirs for the millions of pilgrims who come to bath in the Ganges River. Hand-carved out of single pieces of eucalyptus wood and painted in a traditional dotted pattern, the twelve-piece set in my collection includes the Holy Family, the Three Kings, a venerable shepherd and five delightful creatures blending the real and mythological, which appear to be a donkey, camel, sheep, calf and dog.

Nesting dolls, a toy symbolizing Russia around the world, often depict Nativity scenes in the post-Communist era. Known in their homeland as Matryoski (derived from “Matryona,” a popular peasant name with connotations of The Little Old Lady in the Shoe), these dolls within dolls were the inspiration of a late 19th century Russian arts and crafts movement designer. Each interconnecting piece is hollowed out by hand on a lathe. Nesting dolls have traditionally displayed peasant women in fancy folk dress, but nowadays you can also see portraits of politicians and even religious subjects. The five doll set in my collection from Russian Craftsman Alexander Soshin shows--in descending size--the Holy Family, the Three Kings, the Shepherds, the Flight into Egypt, and a Christmas angel.

The Three Kings take pride of place among the visitors to the manger in creches from the Hispanic world. They are the traditional bearers of gifts on the eve of January 6th, El Dia de los Tres Reyes Magos (Three Kings Day), celebrated in other parts of Christendom as the Feast of the Epiphany. The Magi loom especially large (38 cm. high!) in Guatemalan Folk Artist Jose Canil Ramos ’carved wood crèche set. You will find Three Kings, two sheep, but no shepherds in a smaller Nativity set of painted wood block figures in the distinctive style of Salvadoran folk artists from the village of La Palma.

Manger scenes are a popular theme for Peruvian retablos, painted wooden boxes with doors that open to display story-tellling arrangements of figurines. “Retablo” comes from the Latin term “behind the table (altar),” since this folk art genre evolved from the portable altars carried by missionaries in the Spanish Colonial era. The Nativity retablo in my collection is the work of Claudio Jimenez Quispe and his family, who belong to the Quechua people, descendants of the Incas. Claudio’s wife makes the boxes, he molds the figurines out of potato flour and gypsum, and other relatives paint them with brushes made from the hairs of family cats! In this bustling Quechua Nativity retablo, farm animals (and a llama) jostle to get closer to the Baby Jesus, while country folk in traditional Quechua bombin bowler hats bring gifts of a sheep, a shirt, a rooster, and a watermelon.

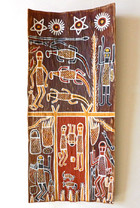

One of the more unusual cross-cultural Nativity scenes in my collection is a bark painting by an unknown Aboriginal artist from the Djinang people of Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory of Australia. Painted in natural ochre earth pigments on the inner surface of a Stringybark Eucalyptus tree panel, the Holy Family inhabit a russet rectangle at the bottom of this semi-abstract image with cross-hatched patterning typical of Arnhem Land Aborginal art. Woven plant-fibre dilly bags store food and possessions. Hunting dogs fill in for the ox and ass at the manger. Hunters substitute for the shepherds, welcoming the Baby Jesus with gifts of tools, weapons, and fresh game--the highly-prized goanna lizard--on this special night ablaze with stars.

In countries with established styles of manger-making, modern artisans remain true to their traditions in innovative ways. German Woodworker Eckart Henzler creates “tree truck books” with pop-out Nativity figures in a sleek, minimalist style from single log blocks found in the forests near his home in Northern Bavaria, carefully preserving the decorative lines and grain of his material. In the hand-carved marbled beech wood crèche in the collection, Henzler has tied together three rough-hewn “pages” that fold out, accordion-style, to form the backdrop for a traditional manger scene whose pieces can be fitted back into holes in the panels for safe-keeping.

Berlin-born Woodcarver Gunther Keil brings together the best of Old and New World folk art in Nativity sets made in a traditional American style with distinctive European touches, using wood from the farm where he now lives in the Finger Lakes region of central New York. Keil’s whimsical figures, cut out in silhouette and colored with natural dyes, appeal to the child in all of us. The 18-piece set in the collection can be arranged in different ways to show the key events of the Christmas story from the Annunciation to the Flight into Egypt, then, packed away in the stable with folding doors that doubles as a "toy" box!

Contemporary creche-creators sometimes employ the the same functional designs of household items to make no frills Nativity scenes like one Scandinavian modern set from Sweden in my collection. The materials may be new or off-beat. Arizona Potter Daina Meyer has transformed the ceramic stems she attaches to wine glasses into tubular glazed earthenware creche figures. American Metal Artist Don Drumm pioneered the use of cast aluminum in contemporary sculptural installations in libraries, hospitals, and churches in Akron, Ohio and makes miniature Christmas images in the same lightweight metal.

Less is more in the minimalist manger scenes of German Designer Oliver Fabel and his British counterpart, Sebastian Bergne. Fabel's creche consists of plain wooden blocks, which, except for the crib and Christ child, are of similar size like pieces in a Jenga game, identified by printed labels, reading "Mary," "Joseph," "Shepherd," "King," "Ox," and "Ass." Bergne takes a different approach, letting the viewer decide just who is who in his Bethlehem manger scene by the shape, color or placement of unmarked beech wood pieces, drawing on what his workshop calls “our learned experience from exposure to thousands of nativity images, toys, and Christmas cards over the years.” When stored in their "stable" box, the figures resemble an abstract painting by Dutch Modernist Piet Mondrian!

The globalization of crèche creation has brought about such a rich mixing and mingling of national styles that it is sometimes impossible to guess the country of origin of some Nativity sets these days without a trained eye. One Christmas display of brightly-colored wooden cut-outs of the Holy Family, the shepherds, and the Three Kings with an accompanying theater proscenium-styled stable came into my collection identified as a folk art piece from Scandinavia. It had really been made half a world away in Sri Lanka!

Camordino Mustafa Jetha ("Dino")

Unknown Cameroonian Potter

Duangkamol Srisukri

Zhang Wan Long

Unknown Indian Artists

Alexander Soshin

Jose Canil Ramos

La Semilla de Dios Workshop

Claudio Jimenez Quispe and family

Unknown Artist of the Djinang People

Eckart Henzler

Gunther Keil

Unknown Swedish Artist

Daina Meyer

Don Drumm

Oliver Fabel

Sebastian Bergne

Minimalist Nativity set in storage box