Polish Poster Art

Amid the devastated cityscapes of Post-World War II Poland, they were viewed as “flowers in the empty spaces.” Posted in the hundreds on the walls of ruined buildings and the fences around construction sites, public notices for cultural events with eye-catching designs added splashes of color to streets devoid of commercial advertising with nothing to see but the monotonous red of Communist Party propaganda banners. In the absence of a real art market in the new Soviet Bloc nation, artists willingly took on official commissions for promotional signs, ensuring themselves of a ready-made audience for their work. Out of this unique combination of circumstances the world-renowned school of contemporary Polish poster art was born.

The poster as an art form originated in Belle Epoque France with the invention of new technologies for color lithography. It was eagerly embraced by turn-of-the-20th-century Polish artists associated with the Young Poland movement in the more liberal Habsburg-controlled regions of partitioned Poland, where nationalist cultural events were promoted with placards combining Art Nouveau styling with folk art motifs. In the interwar period in a restored Poland, graphic artists like Tadeusz Gronowski (1894-1990) set high standards for commercial art with advertisements in a bold Art Deco manner. This was a heritage poster-makers in the Communist era would draw upon in challenging clichéd Socialist Realist imagery imported from the Soviet Union.

Henryk Tomaszewski (1914-2005), one of the founding fathers of the modern school of Polish poster art, has described how it all began with a telephone call from the propaganda section of Film Polski in the early years of the Communist regime. The government-run cinema agency wanted to know if he would be willing to make posters for American movies they were planning to distribute. After conferring with colleagues, Tomaszewski agreed on the condition they be allowed to create designs of their own choosing rather than simply replicate Hollywood images in a way more acceptable to cultural bureaucrats. That odd bargain reaped benefits for both parties.

Special courses in the new “street art” genre were set up at the Warsaw Academy of Arts in 1952, taught by Tomaszewski and fellow graphic designer, Josef Mroszczak (1910-1975), where students were encouraged to develop individual styles of poster-making for movies, theater, the circus, and other public events. Their daring graphics and striking imagery attracted global attention in 1966 at the first International Poster Biennale in Warsaw. Two years later, the first museum in the world devoted exclusively to posters opened in the Wilanow district of the capital. Polish pundits quipped that posters had joined coal and avant-garde cinema as one of the country’s leading exports.

Polish poster-makers found ways to get around official censorship though the use of symbolic imagery and surrealistic exaggeration, as can be seen in Jerzy Czerniawski’s classic 1976 film poster for the crime drama, Before the Day Breaks, where a human profile perfectly conforms to the sole of an oppressive boot. This art of ironic indirection, where the poster maker seems to share a hidden message with more knowing viewers relies on the subliminal associations we all have with certain images and gave Polish posters a visual richness absent from purely informational notices. This artistic strategy of subversive signs and symbols once born out of political necessity remains a defining characteristic of Polish poster art in the Post-Communist era.

If efforts to outwit literal-minded cultural watch dogs with ambiguous designs seemed like a clever game of hide-and-seek in the final decades of Communist rule, making street art became a deadly serious business in the aftermath of the 1981 government crackdown on the independent Solidarity labor union. Poster artists used whatever means were at hand to print illegal notices in a visually compelling style, spreading news of the banned movement and its underground activities. The placards often carried what had become the universally-recognized, red and white Solidarnosc logo, whose expressively scrawled lettering by Poster Artist Jerzy Janiszewski evoked a marching column of flag-bearing workers.

The collapse of the Communist regime, following free parliamentary elections in 1989, spelled the end of the system of state patronage in which poster art had flourished. Cash-strapped cultural institutions stopped commissioning artistic promotional materials. Huge commercial billboards with poor quality, consumer-titilating photos and sex-and-guns Hollywood movie advertisements competed for the same city spaces where posters once hung in solitary splendor. What has kept Polish poster art surprisingly buoyant in the choppy transition to a free market economy is the growing interest among international art-lovers in these graphic works as desirable collectibles.

Given the country’s centuries-old Roman Catholic heritage, Polish graphic artists in the Communist era made use of Christian symbols. The earliest poster in the Collection, designed by Antoni Machalak and printed in the U.S., commemoratives the 1966 millennium of Poland's conversion to Christianity. He gives pride of place to the Black Madonna icon in Czestochowa, the country's most venerated sacred image, displayed above the traditional national emblem of a crowned eagle in defiance of the Warsaw authorities who had stripped the bird of its regal trapping and wanted to mark the event simply as the foundation of the Polish state. This national icon still resonates today for graphic artists like Ryszard Kaja who created a minimally modern but instantly recognizable image of the Virgin Mary and Christ Child for a 2018 travel poster

In the twilight years of Polish Communism, religious motifs enriched the language of visual metaphor in intriguing ways. The scarred donkey on Grzegorz Marszalek’s 1981 poster for Christ Stopped at Eboli brings to mind Christ’s entry into Jerusalem and subsequent suffering, evoking the central themes of this Italian drama of Fascist-era repression. In a placard from 1987, Witold Dybowski encapsulates the conflict between colonialist ambitions and missionary ideals in the Hollywood feature, The Mission, in a stark image of slain doves. Another dove flies free from bound and floating hands, suggesting Noah’s Ark, in Andrzej Pagowski’s design for The Last Ferry, a 1989 film about Polish passengers on a cruise ship fleeing the crackdown on Solidarity.

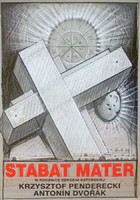

Crosses plain and fancy, whole and broken, Latin and Orthodox, are used as shorthand in Polish posters for cultural events with religious appeal. They appear as folds in music sheets blown across a church-studded landscape in a poster by Leszek Wisniewski for a 2006 sacred music festival in the pilgrimage center of Czestochowa. A cross forms both the bow and the strut of a violin in a placard for the same international music event in 1996 by the Lithuanian-born poster-maker, Stasys Eidrigevicius. Another of the artist’s whimsical figures carries beams for a cross--a religious “art object” in the making--in a notice for a 1994 sacred art triennale. Bulky wood block crosses dominate an abstract object arrangement on a poster by Franciszek Starowieyski (1930-2009) for a concert in 1999 devoted to musical settings of Stabat Mater.

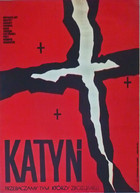

Cross forms also serve as memorial markers for the victims of modern Polish history. In a commemorative poster by an unknown artist, a black cross-shaped gash bleeds white on a field of red, the Polish national colors, evoking the mass graves of Polish officers and civilians executed by the Soviet secret police in 1940 at Katyn Forest. The number “7” in December 1970 extends into a cross in a memorial placard by Krystyna Janiszewska marking the 10th anniversary of demonstrations on the Baltic Sea coast in which over 40 people were killed. The hammer in the Polish Communist Party emblem has been transformed into a truncated cross in a 25th anniversary poster by Jacek Cwikla honoring protestors slain in Poznan in 1956.

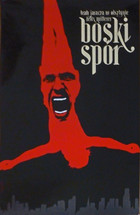

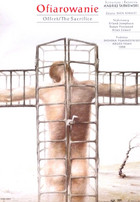

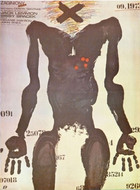

Variations on Crucifixion scenes suggest martyrdom, human rights abuses, and more controversial meanings. A bound, spread-eagled man on a 1975 film poster by Pagowski for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, the classic American film set in a mental institution, equates electric shock treatment with crucifixion. Blood stains on a white shirt suggest the torso of Christ on the Cross in another Pagowski placard for the 1981 Solidarity-themed film, Man of Iron, from Polish Director Andrzej Wajda. Pagowski, literally, turns Crucified Christ imagery on its head in a third poster for Divine Dispute, a 2012 Polish theater production of a modern Austrian mystery play, where Satan defends humanity in a divine court. There are intimations of the Suffering Christ, as well, in the nude figure in a cruciform cage on Roman Kowalik’s 1994 poster for The Sacrifice, a metaphysical fable from Russian Director Andrei Tarkovsky

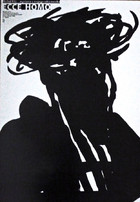

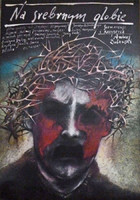

The Crown of Thorns motif appears on posters for an 1990 art exhibit devoted to Baroque Sculptor Johann George Pinzel; on a 1981 placard by Jan Jaromir Aleksiun for a play based on The Master and Margarita by Russian Novelist Mikhail Bulgakov; and on a poster with an abstract head of Christ by Michal Klis for the 2011 Ecce Homo art show. Pagowski has appropriated this image of Christ's Passion for his own symbolic ends in a second design for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, where Lead Actor Jack Nicholson wears a crown of shock therapy wiring; on a 1988 poster for the Polish sci-fi cult film, On the Silver Globe, about an astronaut welcomed as the Messiah on another planet; and in a portrait of the woeful protagonist of Little Judas, a 2010 Polish theater production based on a 19th century family saga by Russian Novelist Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin.

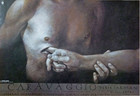

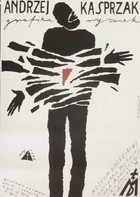

Allusions to the wounds of Christ, a traditional object of Catholic veneration, also add symbolic resonance to poster designs. The prolific Pagowski presents a schematic torso, suggestive of the Shroud of Turin, as his defining image for the 1982 film drama, Missing, about an American writer who disappears during the Chilean military putsch of 1973. A probing finger explores the wound in Christ’s side in Wieslaw Walkuski’s poster for British Director Derek Jarman’s 1986 biopic about Italian Baroque Master Caravaggio, recreating his painting of The Incredulity of Saint Thomas. A throbbing triangle of red in a splintering human form on Roman Kalaras’ placard for an 1988 exhibition devoted to Polish Artist Andrzej Kasprzak also brings to mind the spear thrust into Christ’s side at the Crucifixion, while a poster for a 2009 play about John the Gospel writer by Robert Czerniawski offers an abstract portrait of Christ as a bleeding Man of Sorrows.

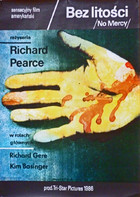

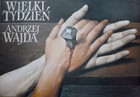

Other images of blood-drenched palms and nail-pierced hands, associated with the Crucifixion, take us to deeper levels of meaning in posters promoting films, plays, and opera productions with tragic, often violent, storylines. Blood gushes from a wounded hand on Marszalek’s 1988 poster for the American crime thriller, No Mercy. The beads of a broken rosary fall from a palm like drops of blood on a Pagowski placard for a 1990 production of Halka, a classic opera from 19th Century Polish Composer Stanislaw Moniuszko about a seduced and abandoned peasant maiden. Walkuski leaves little to the imagination in his unsettling image of the hand of man and woman nailed together on a cross for Holy Week, a 1995 film drama from Director Wajda about Jewish-Christian relationships during the 1943 Warsaw ghetto uprising.

The Star of David functions on posters in much the same way as cross imagery to indicate artistic and commemorative events related to Jewish culture and history. A deeply shadowed hand incised with the emblem dominates a 1986 film poster by Janusz Oblucki (1956-2013) for The Smell of Quinces, a Yugoslav drama about a Nazi sympathizer’s fatal attraction to a young Jewish woman. Mieczyslaw Wasilewski sets the Star of David ablaze in a monochrome 1993 poster marking the 50th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. It forms the triangular base of a balalaika whose dove-sheltered fret suggests Jacob’s Ladder in Ryszard Horowitz’s advertisement for the 15th Jewish Cultural Festival in Krakow in 2005. An inquisitive eye peers out from a Star of David-edged peep hole in an placard by Mieczyslaw Gorowski (1941-2011) for a 1989 exhibition on Jewish-themed poster art.

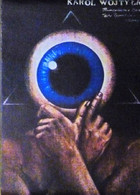

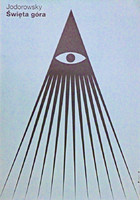

Pagowski makes the All-Seeing Eye of God motif more explicit in his 1984 placard for Ruth (Wedle Wyrokow Twoich), a film drama about a Jewish girl who survives by her wits in Nazi-occupied Polish. He had used the same motif of the Eye of Providence a year earlier in a theater poster for Radiation of the Father, a philosophical drama about God as humanity’s perfect paternal image by Karol Wojtyla (better known as Pope John Paul II). It appears again in a different variation on a placard for the same papal play by Starowieyski. The All-Seeing Eye also stares out at us from Adam Kilian’s design for a 2000 production of The Supposed Miracle or Cracovians and Highlanders, considered to be Poland’s first true opera, and from a 2009 poster by Joanna Gorska and Jerzy Skakun for Holy Mountain, a surrealist Mexican film about the quest for enlightenment.

No survey of contemporary Polish poster art would be complete without considering images of the nation’s now-sainted favorite son: John Paul II. They range from realistic portraits like Wieslaw Grzegorczyk’s brooding study of the aging pontiff on a 2002 poster. marking a papal pilgrimage to Poland to Klis’s quick-sketch, line-drawing on a 1998 placard commemoratiing John Paul II’s twentieth year in the Vatican to a surreal image of the Pope as a dove of peace on a poster from Kalaras for an exhibition of papal pilgrimage memorabilia. The Pope's connection to an event is often signaled just by the inclusion of his famous bent crucifix-topped crozier in the poster design, as we see in Wisniewski’s notice for a 2002 exhibition on the history of Poland’s clergy and a placard from Grzegorczyk for a sacred music concert in 2011, marking the 10th anniversary of the Pope’s visit to Rzeszow, where his trademark staff rises above floating organ pipes.

In the final decade of Communist rule, Poland’s powerful Catholic hierarchy made common cause with the country’s disaffected cultural community, promoting modern art in church venues like the Fra Angelico Gallery at the Archdiocesan Museum in Katowice, inaugurated in 1986. The church-sponsored exhibition space organized national competitions for works of contemporary graphic art on the theme, Toward Values, advertised in two minimalist monochrome posters in the Collection from Kalaras, presenting a face with features formed from the Crucified Christ and a Christ-like figure bent under the weight of a ladder to heaven, casting the shadow of a cross. A third symbolically-stylized Kalaras placard for a 1991 exhibition in the Katowice gallery on the theme of Transcendence shows a finger under a floating halo pointing toward heaven.

As Poland has veered toward the right under the leadership of the populist Law and Justice Party, passing legislation in 2018 that would make it a criminal act to suggest the country shared any responsibility for Nazi crimes committed on its territory, it remains to be seen what impact restrictions of this kind will have on the country’s public arts scene and the entente cordiale between the Church and the artistic intelligentsia. One warning signal came in May 2019, when an LGBTQ rights activist was arrested and threatened with up to two years in prison under a Polish law forbidding “publicly insulting religious feelings or desecrating a ritual object,” after she displayed a placard of the Black Madonna of Czestochowa with a rainbow halo. Having endured one form of censorship, Poland’s long-suffering and ever resourceful poster-makers may now be faced with new challenges to their hard-won artistic freedom.

Jerzy Czerniawski

Antoni Michalak

Ryszard Kaja

Grzegorz Marszalek

Witold Dybowski

Andrzej Pagowski

Leszek Wisniewski

Stasys Eidrigevicius

Stasys Eidrigevicius

Franciszek Starowieyski

Unknown Polish Artist

Krystyna Janiszewska

Jacek Cwikla

Andrzej Pagowski

Andrzej Pagowski

Andrzej Pagowski

Roman Kowalik

Stasys Eidrigevicius

Jan Jaromir Aleksiun

Michal Klis

Andrzej Pagowski

Andrzej Pagowski

Andrzej Pagowski

Andrzej Pagowski

Wieslaw Walkuski

Roman Kalarus

Robert Czerniawski

Grzegorz Marszalek

Andrzej Pagowski

Wieslaw Walkuski

Janusz Oblucki

Mieczyslaw Wasilewski

Ryszard Horowitz

Mieczyslaw Gorowski

Andrzej Pagowski

Andrzej Pagowski

Franciszek Starowieyski

Adam Kilian

Joanna Gorska/Jerzy Skakun

Wieslaw Grzegorczyk

Michal Klis

Roman Kalarus

Leszek Wisniewski

Wieslaw Grzegorczyk

Roman Kalarus

Roman Kalarus