Tyrus Clutter

Tyrus Clutter is one artist in the Sacred Art Pilgrim Collection who is not afraid to court controversy. With intelligence, honesty, and a good deal of humor he looks at the way imagery has been denied, ignored, used, and abused in Christian communities. Clutter not only challenges notions of what is “appropriate” sacred art but touches on important issues of who Christians designate as saints and sinners and where they draw dividing lines for admittance to their “households of faith."

Clutter grew up in a church, where his fellow Christians were people of the Word not the image, and popular pictures like Warner Sallman’s Head of Christ were accepted only as “tools of evangelism.“ As Clutter matured as an artist, he found a way to come to terms with his religious past, creating works of art, using image and word. In his own Head of Christ, he transforms Sallman’s anodyne portrait into something rich and strange by overwriting the face of Jesus with barely readable lines of print. In The Aflictions of Job, Clutter paints an image of the beleagured biblical figure on the pages of a 19th century Hebrew edition of the Book of Job, where the underlying text is still visible through the surface watercolor and casein image. In the five-color polyester plate lithograph, Theotokos, Clutter superimposes an image of the Annunciation from the outer doors of 15th Century Flemish Painter Hugo van der Goes' Pontinari Altarpiece on top of the artistically-altered text of John 1:14 (KJV), beginning with the famous words, "And the Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us..."

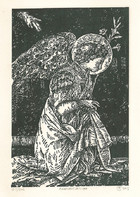

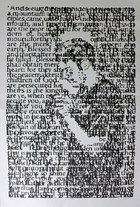

Clutter is especially interested in creating "palimpsest" effects, a reference to old under layers of text bleeding through new writings on parchments scraped for reuse. The coming together of multiple language fragments to form images adds to what the graphic artist calls the "density of meaning" in his prints. In the woodcut, Blessed, the central praying figure is created entirely out of overlapping words taken from the Beatitudes in Christ's Sermon on the Mount, recorded in Matthew 5:1-12. The face of the suffering Jesus in Vera Icon is formed from multiple layers of text found in the traditional Roman Catholic devotion of the Stations of the Cross, where at the sixth stop on the road to Calvary, a pious woman of Jerusalem finds a miraculous portrait of Christ imprinted on the cloth she used to wipe his face.

The Florida-based artist was inspired by writings of the Early Christian Desert Fathers, describing how we should look for the face of Christ in everyone we meet, to creat a color viscosity intalgio print series, pairing well-known depictions of Jesus with pictures of famous historical personalities—both good and bad--like the double "palimpsest portrait" in my collection of the Sallman Head of Christ with an image of American Civil Rights Leader Martin Luther King, Jr. The layered texts in the prints come from the 4th century writings of these Egyptian hermits and monks, whose message, says Clutter, can be summed up in one phrase: “We should treat everyone with the dignity and respect with which we would treat Jesus.”

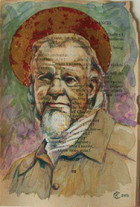

In a watercolor series, certain to raise eyebrows, titled Saints, Sinners, Martyrs and Misfits, Clutter presents a motley group of notable (or notorious, if you so choose!) personalities, decked out in all the artistic trappings of sainthood. They include figures as diverse as Evangelical Apologist C.S. Lewis, French Philosopher Michel Foucault, Conservative Family Activist James Dobson, and Gay Episcopal Bishop Eugene Robinson. Because these figures have been elevated to saint-like status by admirers on both sides of the culture-war barricades, Tyrus depicts them all with gold leaf halos in iconic-styled portraits, painted in watercolor and casein (on book pages, of course!) My current picks from among Clutter's "canonized" notables are Evangelical Theologian Francis Schaeffer, U.N. Secretary General Dag Hammarskjold and Sophie Scholl, executed from her involvement in the anti-Nazi White Rose movement.

Clutter has honored a handful of his modern saints in hand-crafted altarpieces, which resemble the found-object assemblies of American Artist Joseph Cornell (another of Clutter’s contemporary holy men.) When I bought Clutter's homage to Georges Rouault, Altarpiece & Reliquary to St. Georges, I received “user” instructions for putting it all together, explaining where to place the shards of stained glass, the engraving tools, and tiny vials of wine and bread, which were packed apart from the actual “reliquary.” As I studied the text blocks in Rouault’s handwriting and the painted copies of his artwork on the doors, I could see making this unusual wooden construction was an act of devotion for Clutter, whatever his conservative Protestant roots!

Sharp-eyed viewers will notice the St. George, depicted on front of the Rouault altarpiece is a rendering of the French artist in the nude. Fans of Protestant Theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Schaeffer, Lewis, and Novelist Flannery O’Connor, who are the subjects of similar altarpieces will, no doubt, be shocked to see the objects of their admiration portrayed without clothes. Clutter defends this artistic choice, as a way to “affirm the humanity of my subjects.” Christian prudery about nudes, he says, is really “a form of contemporary Gnosticism that denies the body in favor of the spirit.” It is a view he shares with figurative painter Edward Knippers. Clutter's woodcuts dealing with the Passion of Christ, certainly, do not conceal anything under fig leaves!

In an era when art shocks viewers just to be shocking, Clutter’s often startling works remain grounded in a Christian message of reconciliation, directed, first of all, to a church too long divided over issues of imagery in worship.

Head of Christ

The Afflictions of Job I

Theotokos

Annunciation

First Fruits

Blessed

Vera Icon

Palimpsest Portraits: Jesus and Martin Luther King

St. Francis of L'Abri

St. Dag (Hammarskjold)

St. Sophie (Scholl)

Altarpiece & Reliquary of St. Georges (closed)

Altarpiece & Reliquary of St. Georges (open)

Elemental

Incarnation

Stations of the Cross: Crucifixion

Complicity

Stations of the Cross: Entombment